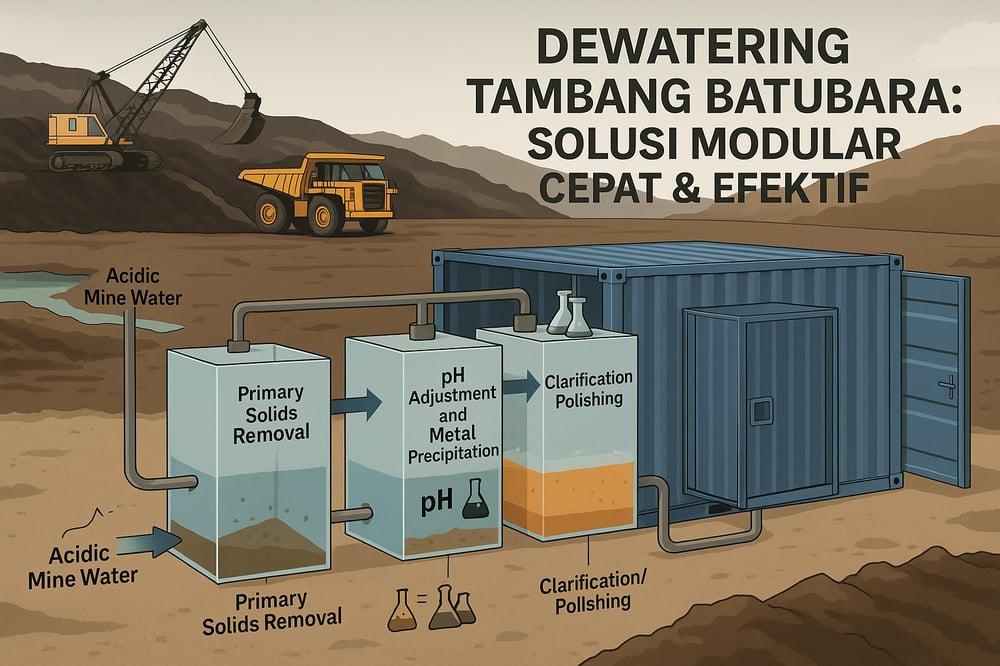

Mine dewatering is getting a plug‑and‑play makeover as containerized units stitch together settling, pH control, and polishing to hit Indonesia’s tough discharge limits — fast.

Industry: Coal_Mining | Process: Dewatering

The water leaving a coal pit is rarely simple: it’s loaded with suspended solids (TSS, total suspended solids), acidic from exposed rock, and spiked with dissolved metals. Indonesia sets a clear line: pH must be 6–9, TSS ≤400 mg/L, iron (Fe) ≤7 mg/L, and manganese (Mn) ≤4 mg/L (Permen LH 113/2003).

Operators aren’t just aiming for compliance; they often design to exceed it (for example, pH around 8 and TSS in the tens of mg/L) to stay well inside the guardrails. The modern answer is a three‑stage train: primary solids removal, pH neutralization with metal precipitation, and final clarification/polishing — each scaled to the site’s flow and contaminant load.

That approach dovetails with a market shift: mobile modular water treatment was roughly US$1.47 billion in 2024 and is projected to hit about US$3.36 billion by 2033 (~9.6% CAGR), with mining and oil‑gas driving roughly 40% of demand (Global Growth Insights) (Global Growth Insights).

Regulatory targets and treatment train

Designing a modular dewatering plant means sequencing three anchored steps and sizing them to the site. First, solids come out via sedimentation — often with a clarifier. Next, pH is raised to precipitate dissolved metals as hydroxides. Finally, a settling/polishing stage strips out the new sludge to produce stable effluent that typically sits near pH ~8 with minimal metals, handing operators a comfortable buffer over Indonesia’s limits (Permen LH 113/2003).

Primary solids removal (ponds and clarifiers)

Settling ponds — sedimentation basins with 24–72 hours’ retention — are the traditional first line, using gravity to remove the bulk of TSS (>50–80%) and particulate‑bound metals. They’re low cost, high footprint, and in Indonesia, routing mine water through “kolam pengendapan” retention ponds is mandated (Nawasis).

Where space or speed is tight, high‑rate clarification with ballasted flocculation (using microsand to weight flocs) steps in. One well‑documented approach uses polymer‑coagulant and recycled sand to hit surface loadings of ≥25–30 gpm/ft² (gallons per minute per square foot, a clarifier loading metric), with only ~12–15 minutes of detention versus >30 minutes for conventional clarifiers — and routinely drives >90% reductions in turbidity and suspended solids (WaterWorld) (WaterWorld). A mobile reactor treating 5,455 m³/day paired with disc‑filter polishing met permit limits while using about 20× less area than a conventional clarifier (Canadian Mining Journal).

Both pathways lean on coagulants (such as ferric chloride or polyaluminum chloride) and anionic polymers at 1–20 mg/L to accelerate floc growth. In Indonesian bench tests at a gold mine, combining coagulant/polymer with Ca(OH)₂ dropped turbidity from ~42 to 26 NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Units, a standard turbidity measure) and captured metals into solids (Jurnal Polinema). In compact builds, a high‑rate clarifier paired with a lamella settler provides the necessary residence time within a small footprint.

For dosing precision at this stage, sites commonly deploy an accurate chemical dosing pump alongside mine‑grade coagulants and flocculants, including options such as poly-aluminum chloride (PAC) when coagulation efficiency is critical.

pH adjustment and metal precipitation chemistry

The second stage raises pH, typically with lime (CaO/Ca(OH)₂), to convert dissolved metals into insoluble hydroxides. At pH below ~3–4, metals such as Fe, Al, Mn, Cu, Zn, and Ni remain soluble; raising pH triggers precipitation as solid hydroxides and oxyhydroxides. Lab and modeling studies show zinc begins precipitating near pH 5 (≈92% removed by pH 7.5 and virtually complete by ~8.5); copper begins near ~6 and is fully removed by ~8 (ResearchGate) (ResearchGate). Manganese is slower — only ~50% removed by pH 8, requiring pH ≈ 9 to remove most (ResearchGate).

Operators often move in two steps: first to ~pH 6–7.5 to remove Fe/Al, then to ~pH 8–9 for Cu, Zn, and others. Indonesian field results back the approach: at PT Amman (NTT), raising acid mine drainage (AMD) from pH 3.23 to 8.70 with Ca(OH)₂ plus PAC and phosphate cut Cu from 4.43 to 0.40 mg/L (~91% removal) and achieved pH 8.7 (Jurnal Polinema). Inline mixers or agitated reactors (about 10–30 minutes of mixing) help ensure reaction completion and floc growth. The U.S. EPA reports that two‑stage lime/sulfide schemes “remove practically all polluting metals” from AMD (EPA).

Final clarification and polishing filters

With metals precipitated, the goal is to settle and polish the newly formed sludge. Conventional clarifiers — including lamella, conical, or sludge‑blanket designs — with 2–4 hours of retention can remove >95% of precipitated solids, often producing single‑digit mg/L TSS in the effluent. In a mobile high‑rate system, a lamellar settler followed by disc filters met stringent permit criteria at 5,455 m³/day (Canadian Mining Journal).

Polishing filters — often sand or membrane media — are sometimes added. In that same deployment, Hydrotech disc filters “polished” 5,455 m³/d downstream of the clarifier (Canadian Mining Journal). For grit‑level finishing, sites incorporate sand filtration to capture 5–10 micron particulates. In a separate pilot, a high‑rate clarification train (Actiflo/Hydrex) drove Cu and Zn down to parts‑per‑billion levels at Canada’s Red Lake project (Veolia Water Technologies).

The resulting sludge is a mix of Fe/Al oxyhydroxides and metal hydroxides (and, in ballasted systems, sand). It is collected for disposal or recycling; dry‑solids tonnage scales with influent metals and can reach tens of kilograms per 1,000 m³ when metal is high.

Containerized modular units for remote mines

Increasingly, all of the above is packed into pre‑built, skid‑ or container‑mounted units. Each module handles a discrete step — coagulation, clarification, filtration — and arrives plumbed for plug‑and‑play installation (Veolia Water Technologies) (Canadian Mining Journal). Typical module capacities range from ~1–500 m³/h, with higher flows achieved by adding units in parallel (Canadian Mining Journal).

This model shifts capital to operating expense (via rentals), accelerates permitting by generating data in real time, and can be running within weeks — compared with the year‑plus often needed for permanent builds (Canadian Mining Journal) (Veolia Water Technologies). Veolia reports mobile units dewatering tens‑of‑thousands of cubic meters (e.g., 10,000 m³/day) in sensitive environments, underscoring the approach’s agility (Veolia Water Technologies).

Because mine water loads surge with weather and operations, discrete containerized modules can be added or relocated to match new demands — often considered temporary but, in some cases, applied “much longer than that” (Veolia Water Technologies) (Canadian Mining Journal). In Northern BC’s remote Brucejack mine, a containerized high‑rate clarification system was selected to handle glacial access and deliver strong TSS and metals removal with minimal footprint (Veolia Water Technologies).

Modules can integrate sensors, automation, and the usual supporting ancillaries. The mobile treatment market overall was about US$1.47 billion in 2024 and is growing at ~10% annually, with forecasts attributing ~35–40% to mining/oil/gas and municipal emergency use (Global Growth Insights) (Global Growth Insights). In Indonesia, while public case data are limited, domestic contractors — for example, Adaro’s PT ATM — now offer modular WTP units, and regulators accept them so long as discharge criteria are met.

Sizing, scalability, and on‑site outcomes

A modular plant is scaled by stacking stages sized for the mine’s chemistry and flow. Need 400 m³/h? Run two 200 m³/h modules in parallel. The core remains unchanged: solids removal (via pond or high‑rate clarifier), pH adjustment with metal precipitation, and final clarification/polishing — with lab or pilot data setting chemical dosage. In practice, precipitation typically removes >90% of target metals, and clarifiers with adequate residence time (>2 hours) can push effluent TSS to single‑digit mg/L while holding pH near ~8.

The goal is straightforward: meet Indonesia’s discharge standards (pH 6–9, Fe ≤7 mg/L, Mn ≤4 mg/L, TSS ≤400 mg/L) while handling hundreds to thousands of cubic meters per day (Permen LH 113/2003). Containerized systems make that scalable and flexible — operational within weeks, relocatable, and expandable as conditions change (Veolia Water Technologies) (Canadian Mining Journal).