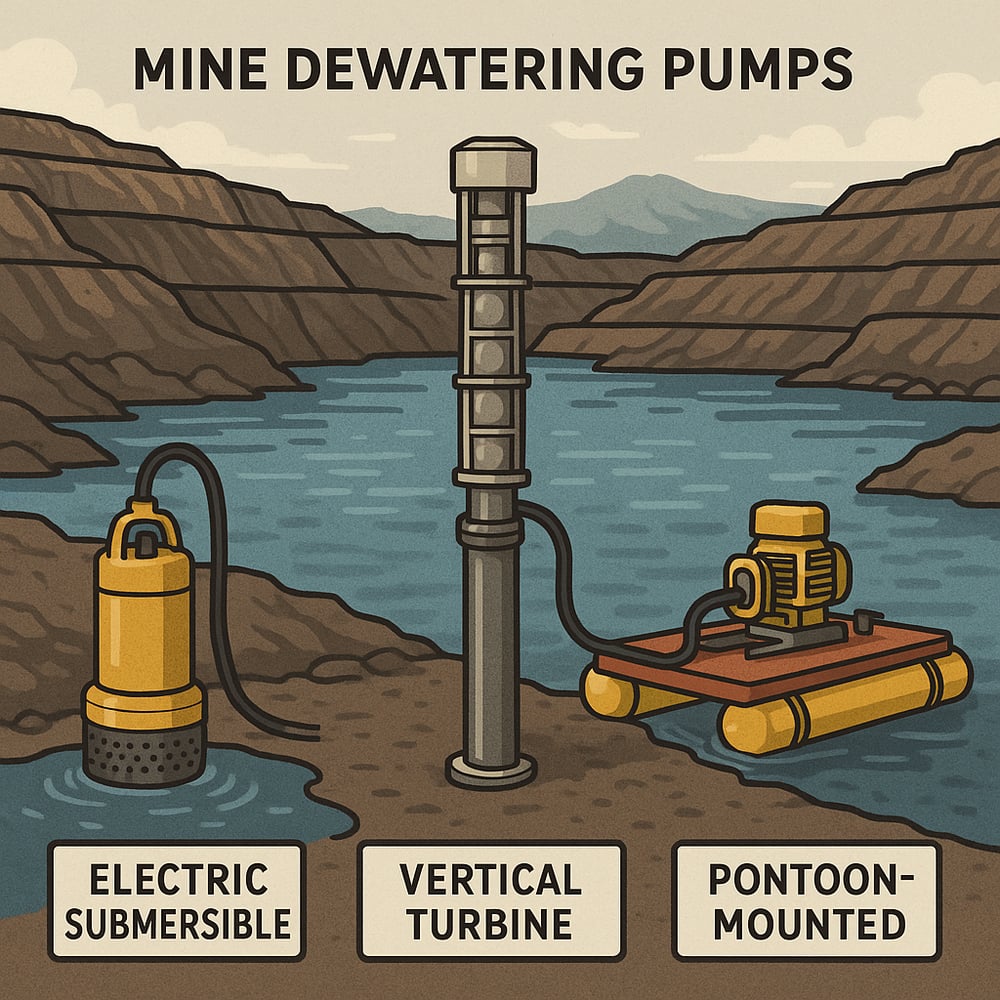

Coal pits take on water fast. Keeping them safe now hinges on three pump archetypes — submersible, vertical turbine, and pontoon-mounted — and on systems engineered to ride out variable flows and high heads without blinking.

Industry: Coal_Mining | Process: Mine_Dewatering

Open pits and underground galleries don’t wait for blue skies. They flood, and fast — especially in rain‑soaked seasons — turning reliable dewatering into a frontline safety and productivity issue for coal operators.

The industry’s workhorses fall into three camps: electric submersible pumps that live underwater and sidestep suction hiccups; vertical turbine pumps that stack impellers to reach big heads; and pontoon‑mounted units that float wherever the water is deepest to move massive volumes. Each comes with sharp trade‑offs, and engineers are pushing toward robust, N+1‑style systems (N+1: one pump in reserve for redundancy) that stay online through surges and high lifts.

Submersibles eliminate suction priming issues by sitting below the waterline (eddypump.com) and can be surprisingly compact — a 7.5 kW unit can measure roughly 33×76 cm and weigh ~60 kg (atlascopco.com). Vertical turbine designs can be stacked for very high heads (studylib.net; im-mining.com). And floating pontoons put pumps at the source in big pits or tailings ponds to handle huge flows without building a fixed station (im-mining.com; im-mining.com).

Electric submersibles: compact, self‑priming units

Electric submersible pumps (motor and impeller submerged; impeller: the rotating element that imparts energy to the fluid) dominate both surface and underground service. Submergence means they self‑prime and avoid air‑locked suction problems (eddypump.com). They’re built as drainage, sludge, or slurry variants with wear‑resistant impellers, and modern designs take on abrasive water and high solids loads (engineeringnews.co.za; eddypump.com).

Typical coal mine units move about 20–200 L/s (72–720 m³/h) at heads up to ~150 m; higher flows use pumps in parallel, while higher heads use pumps in series or multi‑stage options (studylib.net). Specialized high‑head submersibles exist: Hazleton’s HIPPO series reaches up to 2,500 kW (medium/high voltage) and can push acidic, solid‑laden water to very high heads by connecting units in series (engineeringnews.co.za; engineeringnews.co.za).

Fleet scale is real: one Indonesian coal operator runs 33 dewatering pumps (11 diesel and 22 electric) across its sites (adaroindonesia.com).

Durability is now the design center. Makers deploy high‑wear alloys on impellers and liners (eddypump.com), robust seals, and oil‑filled motors to protect windings (engineeringnews.co.za). Leakage sensors and dual seals help prevent water ingress; catastrophic seal failure is the leading cause of submersible failures, and motor rewind alone can exceed half of a pump’s repair bill (engineeringnews.co.za). Trends include cartridge‑type seals, wear‑shield deflectors, and allowing re‑shimming of wear plates to extend service life (pumpindustry.com.au; atlascopco.com).

Submersibles also come with footprint and environmental upsides: no exhaust, quieter underwater operation, and less space than equivalent dry pumps (atlascopco.com). Advances — including modern CFD (computational fluid dynamics) and rapid‑prototype casting — have pushed reliability and maintenance intervals so that leading 10–20 kW units can run fully submerged for extended periods without servicing (atlascopco.com; atlascopco.com).

Vertical turbines: stacked head for high lifts

Vertical turbine pumps (VTPs; “wet pit” designs with a surface motor and impellers below water level) can be single‑ or multi‑stage. Multiple impellers on a long shaft generate very high discharge pressures, so one multi‑stage VTP can replace several large horizontal sets. Weir Minerals adds that VTPs offer a smaller motor footprint at the station and often greater reliability than horizontal alternatives (im-mining.com).

With staged hydraulics, each impeller runs smaller and at lower tip speed, reducing wear. Shaft bearings see uniform loading (gravity acts equally on all sides), producing even wear (im-mining.com). By contrast, a single large horizontal impeller on one side of a casing faces uneven forces and higher peripheral speed, driving faster erosion (im-mining.com).

Anti‑cavitation behavior is a major advantage. In condensate extraction, a long vertical column adds hydrostatic head to prevent vaporization at the lower impeller eye (cavitation: formation/collapse of vapor bubbles that damages metal surfaces) (im-mining.com). The same logic in mine dewatering lets the water column supply net positive suction head, or NPSH (NPSH: pressure head at pump inlet to avoid cavitation), even at high lifts (im-mining.com).

Innovation has pushed into slurry territory. Weir’s Floway® VTSP vertical turbine slurry pumps can handle water with specific gravity up to 1.2 (specific gravity: density relative to water) at high head, using sealed, grease‑packed bearings and an isolator that keeps solids away from seals — removing the need for clean external seal flush water (im-mining.com; im-mining.com).

VTPs are typically fixed on land or in concrete pits, but they also perform on floating pontoons. In one trial, a Floway VTSP on an African mine’s pontoon delivered “no priming required, a low‑maintenance solution and high discharge pressures,” with the long column preventing impeller cavitation (im-mining.com). These multi‑stage builds handle very large flows and heads — several hundred m³/h at several hundred meters of head — though they require civil support (shaft and guide bearings) and maintenance access. Corrosion‑ and abrasion‑resistant steels and Chrome alloys are standard.

Pontoon barges: mobility at the water face

Floating pump barges (or skids with flotation) shine in open pits, tailings ponds, and slimes dams. Mounting pumps and drives on pontoons keeps the intake at the water face for consistent suction conditions and allows relocation as the pit geometry changes (im-mining.com; im-mining.com).

Weir’s Multiflo® pontoons add walkways, cable trays to shore, lighting, and ample service access, paired with heavy‑duty Linatex® suction hoses to resist wear (im-mining.com). Flotation modules can be steel or high‑density polyethylene and are sized to carry 0.5–10 tonne pump sets (and up to 30 ton), with skid‑mounted or containerized options for transport (im-mining.com).

Power can come from on‑board diesel engines or shore‑fed cables. Throughput is significant: an Australian mine installed a 560 kW diesel‑driven pontoon for heavy in‑pit dewatering (pumpindustry.com.au). Pontoons cut civil costs — no concrete pump house or deep well per location — and the choice versus a fixed station turns on topography, volume, head lift, discharge distance, and power availability (im-mining.com). Proper builds meet marine safety standards and can be moved or duplicated as needed.

System design for variable flows and high heads

Mine inflows swing with seasons, storms, and groundwater. Robust systems are over‑designed for peak capacity, with N+1 redundancy and variable‑speed drives (VFDs: power electronics that modulate motor speed) so multiple pumps share base load and ramp as needed. A common template is three identical pumps where two cover normal flow and one sits spare. At very low inflows, engineers guard against “dead‑headed” operation (dead‑headed: zero‑flow condition that overheats fluid) using bypass lines or very low speed.

Head adds complexity. Typical dewatering pumps top out around ~150 m per unit (studylib.net), so higher lifts demand pumps in series (series: one’s discharge feeds the next) or a switch to multi‑stage vertical turbines. Systems must also ensure sufficient net positive suction head — the paper notes “non‑negative suction head” — by using long vertical columns or flooded wells to prevent cavitation (im-mining.com).

Reliability is budget‑critical. Maintenance can consume 35–50% of a mine project’s total costs (mdpi.com), and an unplanned outage can halt production. Designs prioritize materials and layouts to match water chemistry and abrasiveness, with easy access to seals, bearings, and impellers. For submersibles, that means flameproof motors, oil‑filled housings, and seal sensors (engineeringnews.co.za). For vertical turbines, it’s large line‑shaft bearings with grease‑packing and no‑clean‑water seals, as in VTSPs (im-mining.com). For pontoons, quick‑disconnect flanges and winches simplify retrieval. Controls increasingly include remote monitoring, automated level‑based start/stop, and VFDs to trim power draw.

Capacity expectations are high: coal dewatering today often runs to hundreds of L/s at 100–200 m or more (studylib.net; pumpindustry.com.au). A Sykes XH250, for example, can deliver 200 L/s at 220 m head (pumpindustry.com.au). Volumes can be enormous: one PT Adaro unit pumped nearly 3 million m³ of slurry in six months using 25 pumps (adaroindonesia.com). The response is rigorous, site‑specific engineering — hydrology, geometry, cost — and vigilant condition monitoring. IoT and predictive maintenance are emerging: vibration/temperature sensors on bearings, oil analysis, and data analytics aim to catch degradation before failure (mdpi.com; mdpi.com).

The upshot is straightforward. Submersibles cover sumps and underground workings with compact, self‑priming units (eddypump.com; studylib.net). Vertical turbines take on very high heads with staged impellers and can cut station footprint (im-mining.com; im-mining.com). Pontoons add mobility and keep suction conditions optimal in dynamic pits (im-mining.com; im-mining.com). Across all three, robust materials, spares, remote control, and monitoring translate into fewer floods and less downtime (mdpi.com; engineeringnews.co.za).

Sources: Authoritative pump manufacturer publications and mining engineering reviews — engineeringnews.co.za; im-mining.com; pumpindustry.com.au; adaroindonesia.com; atlascopco.com; mdpi.com; studylib.net; im-mining.com; im-mining.com.