Calcium isn’t just a flavor tweak in the mash; it’s a stabilizer for α‑amylase and a quiet pH lever that speeds starch conversion. The right dose of gypsum or calcium chloride can move yields and define beer profiles, from delicate pilsners to hop-forward IPAs.

Industry: Brewery | Process: Mashing

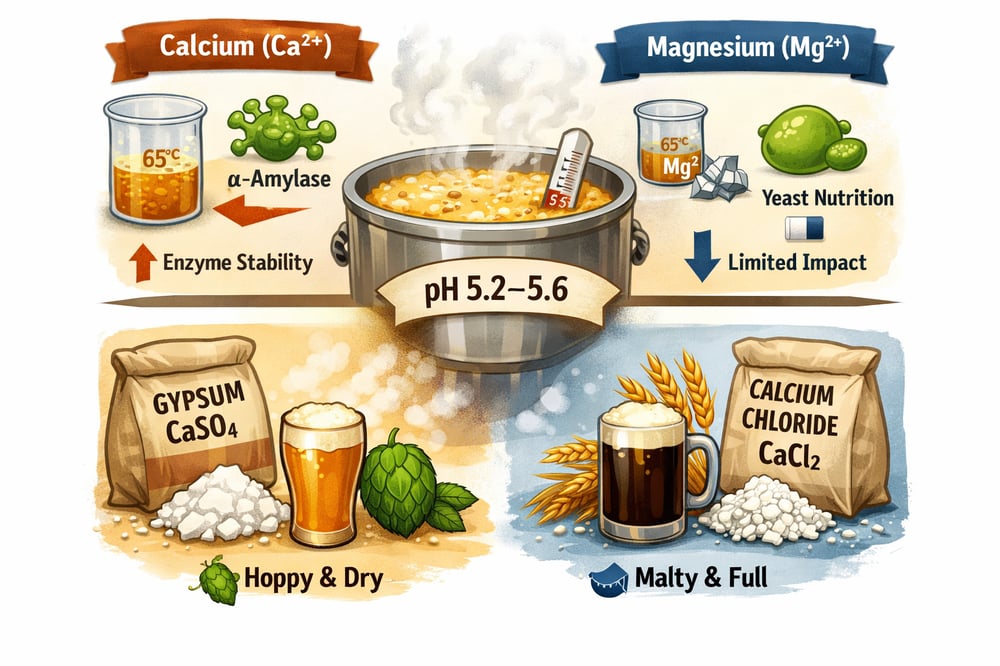

Brewers like to debate sulfate versus chloride for a reason. But underneath the flavor talk is a tougher‑edged biochemical story: α‑amylase, the mash’s workhorse enzyme, is a calcium (Ca²⁺) metalloenzyme and requires Ca²⁺ to remain stable at mashing temperatures (www.murphyandson.co.uk) (www.researchgate.net). Remove Ca²⁺ and α‑amylase rapidly denatures above ~65 °C; as Murphy & Son put it, “Without the protection of Calcium ions, α-amylase is rapidly destroyed at normal mashing temperatures” (www.murphyandson.co.uk).

β‑amylase, by contrast, does not require Ca²⁺ for stability (www.murphyandson.co.uk). The practical upshot: low‑calcium mashes often suffer poorer α‑amylase activity and lower fermentable extract. One mash study found that adding ~100–200 ppm Ca²⁺ (mg/L) to soft water raised alcohol yield by over 50 L of pure alcohol per tonne of grain — roughly a 3–5% increase in yield (www.researchgate.net). In practice, maintaining ~50–150 ppm Ca²⁺ in the mash stabilizes α‑amylase and lets both α and β enzymes work at optimal mash pH.

Enzyme stability and calcium dependence

Ca²⁺ is a critical cofactor for barley α‑amylase and underpins enzyme stability at mash temperatures (www.murphyandson.co.uk) (www.researchgate.net). Experimental removal of Ca²⁺ triggers rapid α‑amylase denaturation above ~65 °C; β‑amylase lacks this Ca²⁺ dependency (www.murphyandson.co.uk). A mash low in Ca²⁺ can therefore underperform on conversion and fermentability.

The yield signal is tangible: adding ~100–200 ppm Ca²⁺ lifted alcohol yield by over 50 L of pure alcohol per tonne of grain (≈3–5% increase) in a soft‑water mash trial (www.researchgate.net).

Magnesium levels and yeast nutrition

Magnesium (Mg²⁺) is less critical in the mash. Malt supplies most Mg²⁺, with brewing sources recommending only ~20–40 mg/L Mg²⁺ in water (brewingforward.com). At low levels, Mg²⁺ contributes mildly to hardness and mash pH buffering, but it is mainly a yeast nutrient — 300+ enzymes require Mg²⁺ (brewingforward.com).

Guidelines caution that Mg²⁺ above ~100–125 mg/L imparts harsh astringency and even laxative effects (brewingforward.com). In practice, wort Mg²⁺ is usually kept well below 30 mg/L. Controlling only Ca²⁺ is sufficient for enzyme optimization, while Mg²⁺ can be left 10–30 mg/L for fermentation health (brewingforward.com).

Mash pH, phosphate buffering, and calcium

Mash pH — commonly targeted at ~5.2–5.6 — is chiefly set by grain acidity and phosphate chemistry. Malts contain phytin (calcium/magnesium phytate), and malt phytase (an enzyme that breaks down phytate) releases phytic acid, which chelates Ca²⁺ and liberates H⁺, buffering the mash. Adding soluble Ca²⁺ salts shifts this equilibrium: Ca²⁺ reacts with phosphates, forming insoluble calcium phosphate, freeing more H⁺ and lowering mash pH (www.biocel.ie).

Each 100 ppm of Ca²⁺ addition can drop mash pH by ~0.1–0.2 units, which accelerates enzymatic activity. As one industry guide notes, "Ca²⁺ reacts with phosphates in the malt…forming insoluble calcium phosphate…leading to a reduction in mash pH. This pH adjustment optimizes enzymatic activity, particularly of α‑amylase and β‑amylase” (www.biocel.ie). Brewers ensure at least 50 ppm Ca²⁺ in the mash to dissolve oxalates and promote yeast nutrition (byo.com).

Gypsum and calcium chloride additions

Brewing salts deliver Ca²⁺ efficiently. Gypsum (CaSO₄·2H₂O) and calcium chloride (CaCl₂·2H₂O) are highly soluble sources; CaCO₃/lime are avoided because they dissolve poorly. Both salts precipitate phosphate equally, so either will drop pH. Typical practice adds ~100–150 mg/L Ca²⁺ (as either salt) to mash water; a study using 100–200 mg/L Ca²⁺ saw the >50 L/t alcohol gain cited above (www.researchgate.net).

Dosing follows flavor goals once the Ca target is set. A rule of thumb: adding 1 g CaCl₂ per liter yields about +120 ppm Ca and +350 ppm Cl (BrunWater), whereas 1 g gypsum per liter yields +230 ppm Ca and +300 ppm SO₄. Both acidify the mash and stabilize α‑amylase. For repeatability, some facilities pair calculations with accurate chemical dosing hardware such as a dosing pump.

Sulfate and chloride flavor balance

While both salts supply Ca²⁺, the anion steers flavor. Sulfate (SO₄²⁻) highlights hop bitterness and a dry finish; chloride (Cl⁻) enhances fullness and maltiness (beersmith.com). Chloride levels >200 ppm make beer taste full and malty, while sulfate >200 ppm emphasizes hop sharpness (beersmith.com).

Historically, gypsum‑rich Burton‑on‑Trent water (high Ca/Mg sulfates) “promote protein coagulation…allow high hop-rate usage…result[ing] in the clear, sparkling ale for which Burton became famous.” (www.precisionfermentation.com). By contrast, Chicago or Dublin waters with higher chloride‑to‑sulfate ratios soften bitterness. Brewers often target a sulfate:chloride ratio ≈1:1 “balanced,” push >1 for hop‑focused beers, and <1 for malt‑dominant beers (beersmith.com).

Style examples and ion targets

An American IPA mash might be built to ~90 ppm Ca, 160 ppm SO₄²⁻ and 50 ppm Cl⁻. In one benchmark 19 L mash, additions of 5 g gypsum + 2 g CaCl₂ produced a final water with ~90 ppm Ca, 160 ppm sulfate, 51 ppm chloride (krugerbrewerblog.wordpress.com). A Bohemian pilsner favors very soft water: roughly 30 ppm Ca, negligible sulfate and moderate chloride (~50 ppm) (krugerbrewerblog.wordpress.com).

A German pilsner water often has Ca ~30 ppm with both Cl and SO₄ around 50 ppm each (krugerbrewerblog.wordpress.com). In a sweet stout, brewers might target ~100 ppm Ca and 100–150 ppm Cl⁻ with low sulfate. Across styles, mash pH near 5.2–5.4 for pale beers or ~5.5 for dark is typical, achieved by balancing grain acidity, buffering ions, and Ca²⁺ addition.

Water profile construction and monitoring

To construct a water profile: obtain the base water analysis, plan the grain bill, and set the desired mash pH (~5.2–5.6). Use brewing software or calculations to determine gypsum/CaCl₂ amounts to reach target Ca²⁺ and adjust SO₄²⁻/Cl⁻. Key targets include Ca²⁺ ~50–150 ppm (at least 50 ppm to avoid “beerstone” byo.com); Mg²⁺ ~10–30 mg/L; SO₄²⁻ up to 300–400 ppm for hoppy beers; Cl⁻ up to 100–150 ppm for malt balance.

For instance, a balanced pale ale might use Ca ~100 ppm with SO₄/Cl ≈1:1, while a dry IPA might push SO₄:Cl ≈3:1. Monitor mash pH with a meter or test papers; the added Ca²⁺ should self‑adjust pH into range. Brewing practice sources also provide recommended ion ranges and style profiles (beersmith.com). Tailoring gypsum and CaCl₂ to hit the enzyme‑optimal Ca²⁺ range (≈50–150 ppm) and the style‑specific SO₄/Cl balance maximizes mash conversion efficiency and delivers the intended profile (byo.com) (beersmith.com).

Regulatory parameters and safety context

Local water regulations provide useful guardrails. Indonesia’s drinking‑water standard (Permenkes 492/2010) allows total hardness up to 500 mg/L as CaCO₃ (roughly Ca <200 ppm) and Cl⁻ up to 250 mg/L (id.scribd.com). Brewers should ensure final wort chemistry is within these limits and below the 200 mg/L Ca guideline cited by health authorities (fr.scribd.com). In practice, most beers operate well under these values.

Sources and further reading

Peer‑reviewed and industry literature underpin the enzyme and water chemistry points above. Enzyme studies and brewing chemistry guides (www.researchgate.net) (www.biocel.ie) quantify Ca²⁺ effects on enzyme stability and mash pH. Brewing practice sources provide recommended ion ranges and style profiles (beersmith.com) (beersmith.com) (krugerbrewerblog.wordpress.com) (krugerbrewerblog.wordpress.com). Indonesian standards are drawn from Permenkes regulations (id.scribd.com). All conclusions above match these data‑driven references.