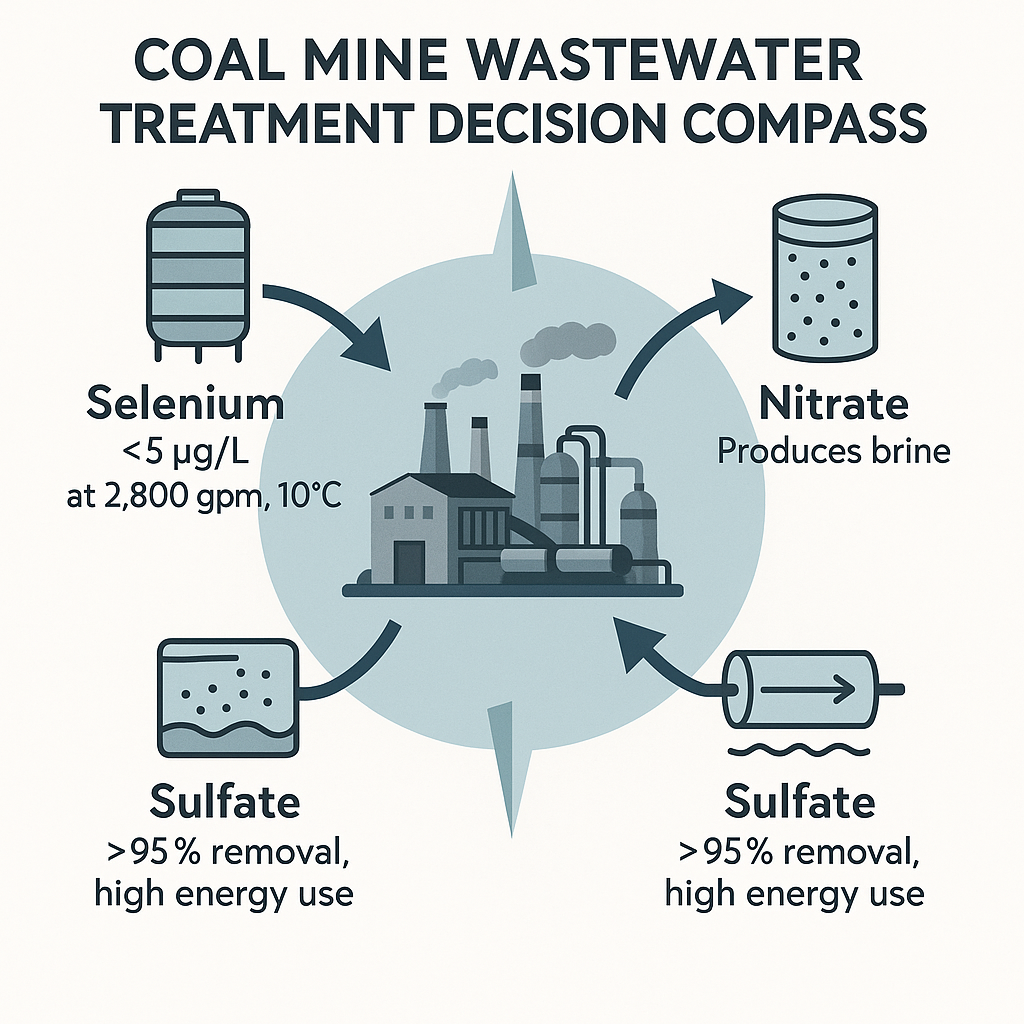

Coal mines face a three-front battle in wastewater: selenium, nitrates, and sulfates. The latest data show biological systems, ion exchange, and reverse osmosis can all hit tight limits — but the right pick hinges on flow, co‑contaminants, waste handling, and cost.

Industry: Coal_Mining | Process: Wastewater_Treatment

At one U.S. coal site, an engineered bioreactor ran at 2,800 gpm (gallons per minute) with 10 °C influent and held selenium below 5 µg/L (micrograms per liter) for 10 months (nepis.epa.gov). In lab tests, zero‑valent iron cut 90% of 1 mg/L Se(VI) in 4–8 hours — but with 1,800 mg/L sulfate and 15 mg/L nitrate, the same 90% reduction took ~50–150 hours (pubs.acs.org). And for sulfate, reverse osmosis clears >95% but pushes brine volumes to 20–30% of feed while running at 200–300 psi (nepis.epa.gov) (www.scielo.org.za).

Here is how the options stack up — and a plain‑English guide to choosing between them without blowing out footprint or OPEX.

Selenium control: biological reactors vs chemical reduction

Biological reactors (BCR/FBR; fixed‑film and fluidized‑bed bioreactors for anoxic reduction) have consistently delivered high removals of both Se(VI) and Se(IV). A U.S. BCR (Luttrell site) recorded ~95% removal for most metals, including selenium (nepis.epa.gov). Gravel‑bed media achieved 98% Se removal with effluent under 5 µg/L (nepis.epa.gov).

Engineered fixed‑film systems such as ABMet have treated 5–1,400 gpm flows, routinely discharging selenium at ≤5 µg/L while also achieving complete nitrate (NO₃‑N) removal (nepis.epa.gov). One full‑scale fluidized‑bed reactor at a coal mine, with 10 °C influent, treated 2,800 gpm and kept Se <5 µg/L over 10 months (nepis.epa.gov). Pros: >95–98% removal, minimal chemical dosing, organic carbon (e.g., methanol) as electron donor, and concurrent nitrate removal (nepis.epa.gov) (nepis.epa.gov). Cons: residence times of hours to days, pH near neutral, periodic media/sludge removal, and ongoing carbon feed and control.

In these configurations, fixed beds and carriers are common; packaged fixed‑bed bio‑reactors and precise methanol feeds via a dosing pump are standard ways to hold setpoints in anoxic operation.

Chemical reduction (ZVI and iron precipitation) relies on zero‑valent iron converting selenate to selenite to elemental selenium under anaerobic conditions (nepis.epa.gov). In lab tests near neutral pH, 90% of 1 mg/L Se(VI) was removed by ZVI in 4–8 hours when competing anions were absent (pubs.acs.org). With 1,800 mg/L sulfate and 15 mg/L nitrate present, reaching 90% removal stretched to ~50–150 hours because sulfate and nitrate compete for iron’s reducing power (pubs.acs.org).

Pros: fast reactions and flexible sizing; iron chemistry is well‑established. Cons: performance drops in high SO₄²⁻/NO₃⁻ waters, and metal‑rich solids and brines require thickening and disposal (nepis.epa.gov) (pubs.acs.org). For solids management, a gravity clarifier is typically paired downstream to settle iron residues and Se‑laden sludge.

Bottom line: both routes can meet <10 µg/L selenium limits; biological trains have demonstrated ≤5 µg/L consistently on large flows (nepis.epa.gov) (nepis.epa.gov), while chemical systems demand tighter pH control and more sludge handling (nepis.epa.gov) (pubs.acs.org). Many sites blend methods — chemical pre‑treatment followed by biological polishing.

Nitrate removal: ion exchange vs biological denitrification

Ion exchange (IX) swaps nitrate (NO₃⁻) for chloride or hydroxide on nitrate‑selective anion resin. At Buckhorn Mine, one full‑scale unit treated ~100 gpm with 12–25 mg/L NO₃‑N (nitrate‑as‑nitrogen) influent (www.wateronline.com). Pros: near‑instant removal to very low levels, compact footprint, well‑understood operation. Cons: brine from regeneration is ~5–10% of treated flow and must be managed; regenerant chemicals add O&M high TDS accelerates fouling (www.wateronline.com) (nepis.epa.gov). Reported IX systems commonly operate between 40–350 gpm for drinking/industrial services (www.wateronline.com).

For packaged deployments, complete ion exchange systems with nitrate‑selective media are standard, with brine waste routed to site handling or off‑site disposal as policy allows.

Biological denitrification uses anoxic bacteria and an organic electron donor (methanol, ethanol, acetate) to reduce NO₃⁻ to nitrogen gas. Packed‑bed and fluidized‑bed systems routinely achieve >95% removal; Severn Trent’s Tetra Denite with methanol feed has hit effluent under 0.5 mg/L NO₃‑N at 6–12 °C (www.wateronline.com). Pros: no brine; end‑product is N₂; donors are relatively low‑cost (e.g., $0.1–0.2/L methanol). Cons: requires minutes‑to‑hours contact time, continuous carbon supply, biomass management, temperature sensitivity (efficiency drops below ~10 °C as noted for FBRs; nepis.epa.gov), pH control, and post‑treatment for biodegradable organics.

OPEX is typically driven by carbon and mixing power; methanol pricing is often cited near ~$0.50–1.00/kg in planning comparisons. For on‑site biology, operators commonly deploy an anoxic stage within a broader biological digestion train to manage carbon and nutrients holistically.

Trade‑off: IX is modular and fast but displaces nitrate into a brine. Biology eliminates nitrate without brine and often achieves <1–2 mg/L NO₃‑N (www.wateronline.com) if space and steady operation are available. Hybrid trains — bulk denitrification followed by IX polishing — are used where practical.

Sulfate removal: reverse osmosis vs biological sulfate reduction

Reverse osmosis (RO) removes >95% of dissolved sulfates and co‑contaminants (TDS, metals, sodium/chloride) in one pass (nepis.epa.gov). At a remote California gold mine, RO operation reduced selenium and chloride — and, by process design, sulfate — from ~60 µg/L selenium in the impoundment to <5 µg/L (nepis.epa.gov). Brine typically equals 20–30% of feed and concentrates SO₄, metals, and TDS (nepis.epa.gov).

Cons: high CAPEX for pumps/membranes; energy‑intensive (200–300 psi common); calcium sulfate scaling drives the need for anti‑scalants or softening; brine disposal requires evaporation ponds or deep‑well options (www.scielo.org.za). Membranes last ~2–5 years and pretreatment (filtration, pH adjustment) is mandatory (nepis.epa.gov). Mine operators typically deploy a brackish RO skid — for example, a brackish-water RO — with upstream pretreatment using ultrafiltration and sulfate scaling control via membrane antiscalants.

Biological sulfate reduction (BSR; anaerobic reduction of SO₄²⁻ to sulfide and elemental sulfur) has posted 92–97% sulfate reduction in mining waters in recent MBfR (membrane biofilm reactor) studies, with rates up to ~3.7 gS/m³·d and, in ideal cases, full conversion to elemental sulfur (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Pros: low O&M, recoverable elemental sulfur or precipitated metals, very low sludge. Cons: larger reactors, carbon source or H₂ gas feed and steady loading, and effluent re‑oxygenation/pH adjustment needs.

Economics: a South African comparison found the lowest operating cost for BSR at ZAR 4.5–11/m³ (~$0.30–0.70) versus R17 (~$1.20) for ettringite precipitation and >R33 (~$2.30) for RO; these figures exclude capital, and RO’s energy plus brine disposal dominated O&M (www.scielo.org.za) (www.scielo.org.za). Regulators often limit sulfate to ~250–500 mg/L; full compliance may require neutralization plus specialized SR‑reactors. For consumables like nutrients and start‑up cultures, operators typically plan a small inventory of wastewater consumables.

Use case split: BSR suits remote or low‑flow sites and passive post‑closure treatment (www.scielo.org.za), while RO is used where footprint is tight or discharge limits demand minimal dissolved load at active facilities (nepis.epa.gov).

Decision guide: matching treatment to mine water

Selection comes down to standards, chemistry, flow, operations, waste, and cost. A practical checklist:

- Targets: meet Se ≤10 µg/L, NO₃⁻ ≤10 mg/L‑N, SO₄ ≤250–500 mg/L for discharge.

- Chemistry: high SO₄/NO₃/TDS hampers chemical reduction and IX, often favoring bio‑based reduction (pubs.acs.org) (nepis.epa.gov).

- Flow & footprint: high flows may suit large bioreactors or IX columns; skids handle small flows (RO/IX) (www.wateronline.com).

- Operations: availability of chemicals, power, labor; climate — FBRs are temperature‑sensitive and lose efficiency at <10 °C (nepis.epa.gov).

- Waste: biology produces biomass; RO/IX/chemical routes generate brines and metal‑rich sludges that need disposal (www.wateronline.com) (nepis.epa.gov).

- Economics: balance CAPEX vs OPEX. Biological denitrification avoids brine and can be cost‑efficient (donor near $0.1–0.2/L methanol; methanol ~$0.50–1.00/kg; power for mixing), while IX uses low‑cost salt but creates brine. For sulfate, BSR’s OPEX (ZAR 4.5–11/m³, ~$0.30–0.70) undercut ettringite (R17, ~$1.20) and RO (>R33, ~$2.30), excluding capital (www.scielo.org.za) (www.scielo.org.za).

Usage examples: deploy IX when compact, guaranteed nitrate removal is needed and brine disposal is workable (www.wateronline.com) — often as a packaged ion‑exchange resin system. Favor biological denitrification when long‑term O&M budgets point to low‑chemical processes (www.wateronline.com).

For sulfate, select BSR when land and retention time are available and OPEX must be minimized (www.scielo.org.za). Choose RO — or ED (electrodialysis) — when very low discharge TDS is required, accepting higher cost and brine handling (www.scielo.org.za) (nepis.epa.gov). Hybrid trains and pilot trials are recommended to match site‑specific chemistry and cost. Containerized pilots, such as rental RO units, can de‑risk design before full build.

All selections should align with Indonesian regulatory limits (e.g., PP 82/2001 water quality classes) and World Bank/WHO guidelines in the absence of local standards.

Sources: peer‑reviewed studies, industry reports and guidelines were used — nepis.epa.gov (nepis.epa.gov) (nepis.epa.gov) (pubs.acs.org) (nepis.epa.gov) (www.scielo.org.za) (www.wateronline.com) (www.wateronline.com) (nepis.epa.gov) (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). All statistics and claims above are from these sources.