Brewers are squeezing more from their grain by tuning crush, temperature rests, and grain‑bed management. Data-backed tweaks — and targeted aids like β‑glucanase and rice hulls — are turning lautering from bottleneck to strength.

Industry: Brewery | Process: Lautering_&_Wort_Boiling

The lauter tun (the vessel that separates sweet wort from the spent grain) lives and dies by physics and cell-wall chemistry. Crack the endosperm too fine and the bed gums up. Skip a 45 °C rest and viscosity spikes. Rake at the wrong time and channels form, leaving sugars behind.

Across studies and manufacturer data, the playbook is consistent: protect husks, control β‑glucans, and manage differential pressure (ΔP, the pressure drop across the grain bed). That mix is delivering ~10% productivity gains and up to 98.7% extract yield in modern systems (GEA).

Here’s what the data says — and how brewhouses are troubleshooting toward lauter runs in the 70–110 minute window for a 60 bbl mash with first‑runoff turbidity below 250 NTU (NTU: Nephelometric Turbidity Units).

Grain milling and husk integrity

Proper milling is the first line of defense. The aim: crack the starchy endosperm while leaving husks mostly intact so they act as a natural filter bed. Excessive fines clog the bed and cause channeling — wort takes “path[s] of least resistance,” leaving some regions unrinsed (MoreBeer).

In practice, a two‑roller mill gap around 0.5–0.6 mm is often ideal. One study found a 0.55 mm gap on a 2‑roller mill produced a grist “comparable to a commercial six‑roller mill,” maximizing husk integrity (GRDC). Brewhouses tune gaps by aiming for ~4–6 pieces per kernel (petals) and avoiding pulverized husk. Measurements confirm it: malts that preserve husk integrity yield faster runoff and higher extract.

When malts are under‑modified — with high zygotic β‑glucans — lautering slows or stalls; an Australian brewing report identified such malts as a main cause of poor lautering (GRDC) (GRDC).

Mash temperature profile and viscosity control

Mash schedule governs enzyme activity and wort viscosity. β‑glucans (cell‑wall polysaccharides prone to forming gummy gels) gelatinize around 50–60 °C unless degraded. A lower‑temperature rest around 40–45 °C activates malt β‑1,3‑1,4‑glucanases (β‑glucanase: enzymes that break down β‑glucans), which “peak” at ~40–45 °C and cut viscosity (Crisp Malt). Skipping this rest risks a choked filter bed.

Proteinases/proteases (optimum ~50–55 °C) act on cell walls, while amylases finish starch conversion (β‑amylase ~62–67 °C; α‑amylase ~71–72 °C) (Crisp Malt). A classic step mash — for instance 45 °C → 50 °C → 65 °C → 75 °C — with ~15–20 minutes at 45 °C and a mash‑out near 75–78 °C is common to lower viscosity.

The link is quantifiable: one study correlated wort β‑glucan with filtration time (r>0.97) and viscosity (r>0.95) (MDPI). Reducing β‑glucan content directly speeds lautering. Modern maltsters often deliver well‑modified malt, yet when β‑glucan runs high, the mash must compensate. Michiels et al. (2023) summarize that enzymes degrading β‑glucan and arabinoxylan “are widely used in the brewing industry to improve wort and beer filtration” (Journal of the Institute of Brewing).

pH and mash thickness matter: pH 5.2–5.6 and 2.5–3.5 L water per kg grain favor enzyme action. A too‑dilute mash elongates lauter time, while a too‑thick mash can compact the bed.

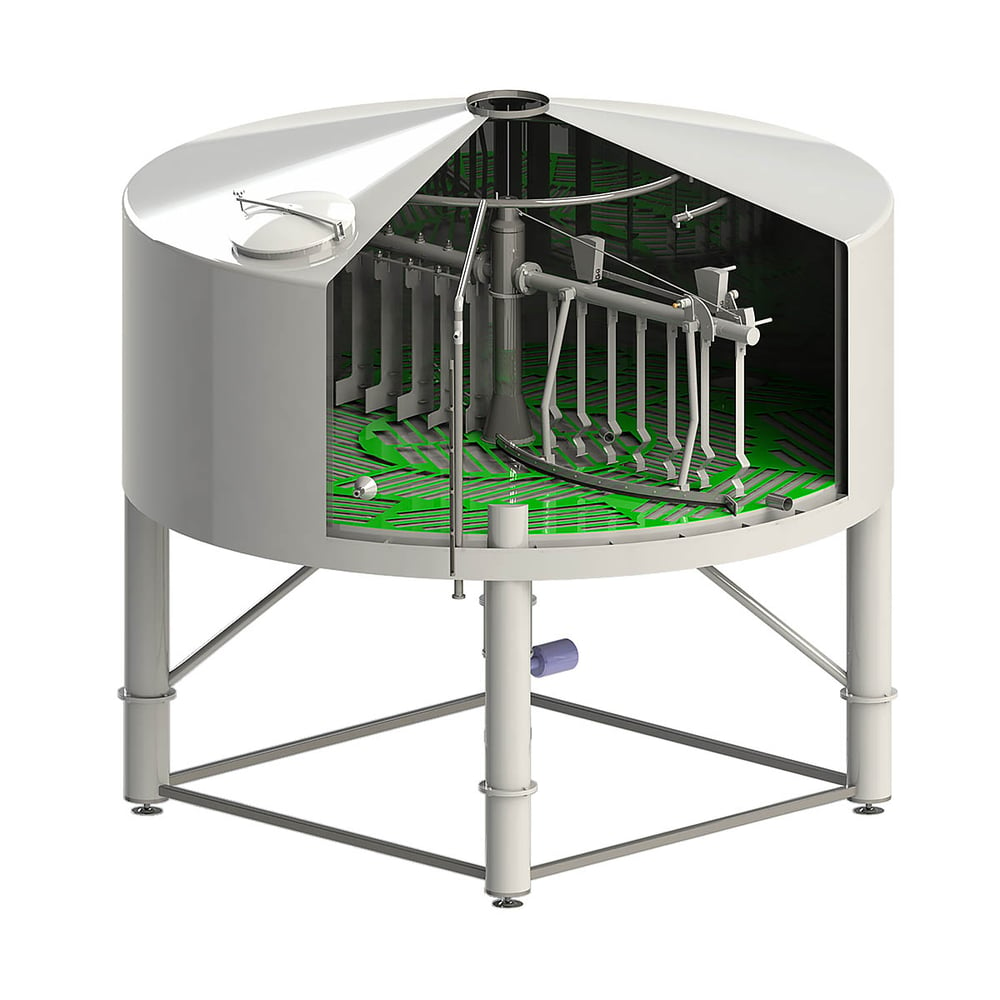

Lauter tun design and grain‑bed management

Darcy’s law (a filtration principle linking flow, pressure drop, and permeability) frames the mechanics. Equipment variables include bed depth, false‑bottom design, and raking. Larger‑diameter tuns tend to run shallower beds — often ~250–380 mm — to balance clarity and flow. False‑bottoms with ≥10–12% open slot area are common; some systems raise this to ~15–18% to speed runoff. A plenum gap (clearance under the false bottom) around 10–20 mm promotes even flow.

Rakes or agitators prevent compaction. According to GEA’s latest design, a rake that lowers late in lautering can maintain “low resistance in the grain bed and prevent channel formation” (GEA). Runoff should start gradually; sudden high ΔP (ΔP >0.3 bar) compacts grains. Keeping ΔP ~0.1–0.2 bar and opening valves slowly helps the bed remain “supersaturated” and mobile (MoreBeer).

The effect of active raking is documented: modern systems with advanced rakes report a ~10% productivity gain and ~98.7% extract yield (GEA) (GEA). Earlier, stagnant rakes could allow 2–3% wort loss to a stuck bed; GEA’s testing eliminated such losses (GEA).

Processing aids: enzymes and rice hulls

Exogenous enzymes are a safety valve when adjuncts or seasonality push gums higher. Commercial blends — typically with endo‑β‑1,4‑xylanase and β‑1,3‑1,4‑glucanase activities — can be pitched to the mash. These hydrolyze cell‑wall polysaccharides and reduce wort viscosity; trials show higher enzyme dose decreases high‑molecular‑weight β‑glucan and arabinoxylan, speeding lautering (Journal of the Institute of Brewing). A β‑glucanase rest at ~45 °C for 15–20 minutes plus a commercial enzyme dose can restore runout in “high‑β‑glucan” malt. An optimal mash schedule identified by Sun et al. (2023) used an α‑amylase:β‑glucanase:protease ratio of 1:2:1 at 44 °C for 38 minutes (MDPI). Accurate chemical dosing (dosing pump) supports consistency when adding such blends.

Rice hulls add structure without extract. Industry practice adds roughly 2–5% by weight when >15–20% of the mash is huskless grains; they “prevent stuck sparges without affecting flavor” (YoLong Brewtech). Field reports include a brewer adding 3% hulls and seeing lautering time drop 18% with stuck‑mash incidents falling to zero over multiple brews (YoLong Brewtech).

Troubleshooting benchmarks and actions

Targets help frame decisions. For a 60 bbl mash, a lauter time of 70–110 minutes and first‑runoff turbidity <250 NTU are desirable. ΔP across the bed should remain ~0.1–0.2 bar. Extraction yield is a key output; well‑optimized systems now report ≥98% of potential extract (cf. <95% in older Lahautering) (GEA, 5 brews per day) (GEA). Modern craft breweries set numeric NTU goals.

- Slow or stuck runoff: Check filtration particle size; a too‑fine crush increases flour. Verify ratio and mash temperature; consider a β‑glucan rest or adding β‑glucanase. Add 2–5% rice hulls for high‑adjunct grists (YoLong Brewtech). Inspect tun design: ensure inlet/outlet paths are clear and recirculate (vorlauf, the step of returning turbid runoff to the mash bed until it runs clear) until clear.

- Low yield/extraction: Verify mash conversion (iodine test). Ensure sufficient recirculation and sparging. Channeling leaves sugars behind; maintaining an inch of wort over the bed (“supersaturation”) helps equalize flow (MoreBeer). Gentle raking during sparge can flush poorly wetted zones. Slightly raising mash‑out temperature can lower viscosity and release more sugar.

- High turbidity/clarity issues: First‑wort turbidity >300 NTU suggests bed breakage. Review crush (fines drive turbidity). A coarser grind or longer recirculation improves clarity. β‑Glucan or polyphenol excess can suspend solids; enzyme treatments (β‑glucanase, cellulose, polyphenol oxidase) and protein‑rest pH control (5.2–5.4) reduce haze.

- Pressure anomalies: If ΔP spikes, slow flow immediately — compaction is likely. Do not force flow; throttle runoff and/or rake to relieve the bed. Keep outlet valves fully open before sparging to avoid suction.

Data‑driven optimization

Runoffs improve when decisions are tied to data — flow rates, ΔP, and turbidity — and to small, cumulative changes: tighter mill calibration, stepped mashes, and judicious enzymes/hulls. One case study replaced a fixed mash schedule with a held β‑glucan rest and a minor mill adjustment, yielding a 22% faster runoff and a 3‑point boost in efficiency. Retrofitting a conventional tun with optimized rake timing and valve control cut lauter time to ~70 minutes and lifted extract to ~98.7% (GEA).

Automation is trending — from rake control to turbidity sensing — but the fundamentals remain: protect husks, lower β‑glucan, and manage ΔP. Relevant Indonesian standards (e.g., SNI for beer) focus on ingredients and safety rather than process specifics; local brewers thus rely on international best practices as above.

Sources underpinning these guidelines include peer‑reviewed and technical references: procedural investigations of lautering (ResearchGate), enzyme impacts on filtration (Journal of the Institute of Brewing), equipment data from GEA (GEA) (GEA) (GEA), correlations between β‑glucan and filtration performance (MDPI), mash‑enzyme temperature optima (Crisp Malt), milling impacts and under‑modification risks (GRDC) (GRDC), practical lautering tactics (MoreBeer), and adjunct‑era aids like rice hulls (YoLong Brewtech).