Commercial brewers overwhelmingly lean on forced carbonation for speed and consistency, dialing in in‑tank stones or in‑line injectors to hit tight CO₂ targets. Precision meters from Zahm & Nagel and Anton Paar verify the numbers, while a disciplined troubleshooting playbook keeps flat pours and gushers off the line.

Industry: Brewery | Process: Filtration_&_Carbonation

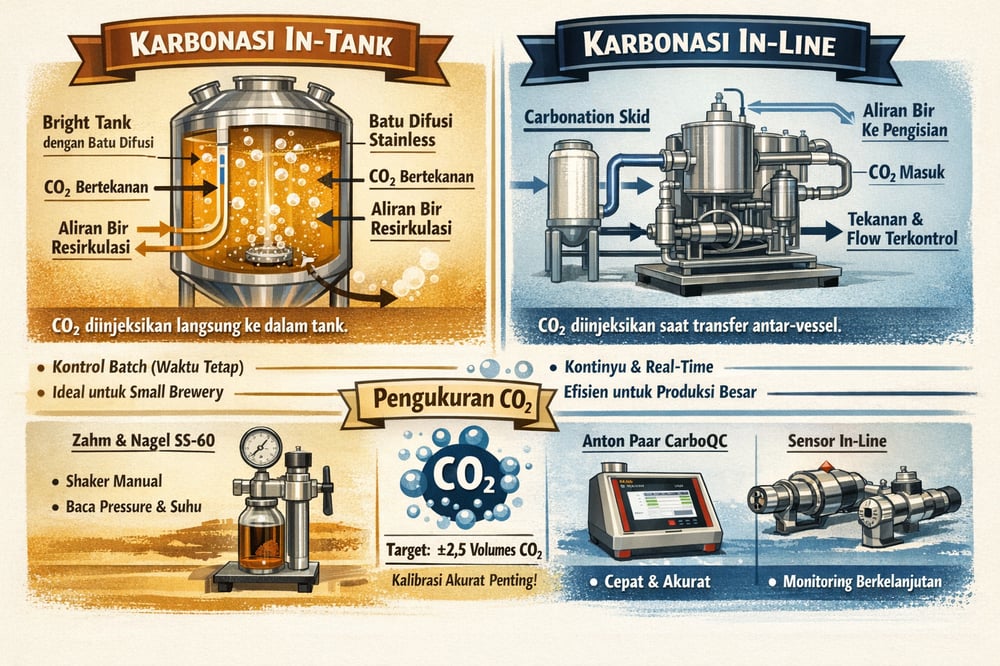

Breweries carbonate beer either naturally (post‑fermentation sugar in sealed vessels) or mechanically (CO₂ forced into beer), and it’s the latter that dominates modern production for speed and repeatability. In‑tank diffusion stones and in‑line carbonators are the two workhorses. Both exploit the same physics: higher pressure and lower temperature drive CO₂ into solution — think roughly 1 bar (≈15 psi) near 0–4 °C to maximize uptake (beerandbrewing.com).

Targets vary by style: many ales sit around ~2.2–2.7 volumes of CO₂ (≈4–6 g/L), while lagers and light beers often run 2.5–3.0 volumes (mebak.org; morebeer.com). For example, at ~4.5 °C and 13 psi (≈0.9 bar) headspace, the beer lands near 2.5 volumes (morebeer.com). Expect packaging losses: on average ~0.2 volumes in bottling and ~0.05 in kegging — so set bright tanks slightly above target (e.g., 2.7 vol for a 2.5 vol bottle target) (morebeer.com). Tiny instrument errors matter: a 0.5 psi gauge offset at 0 °C can skew carbonation by ~0.05 volumes (morebeer.com).

In‑tank stones vs. in‑line injectors

In‑tank “batch” carbonation uses a sintered stainless‑steel diffusion stone on a bright or conditioning tank; the stone creates fine bubbles, while gentle recirculation or agitation helps the beer equilibrate. Running at ~1–2 bar with recirculation, a diffuser can dissolve several g/L of CO₂ in about an hour. By contrast, in‑line systems inject CO₂ directly as beer flows — commonly between a membrane filter and the bright tank (beerandbrewing.com). Some breweries position this step after a membrane filter during transfer to packaging. Bubble size, contact time (longer pipe runs), and controlled pressure are the levers for full dissolution (beerandbrewing.com).

The choice is tactical. In‑tank carbonation is ideal for precise control over a fixed volume, useful when switching styles or fine‑tuning conditioning. In‑line carbonation is continuous, syncing with high‑throughput packaging and enabling real‑time adjustments. Zahm & Nagel notes it makes stones for tanks and carbonators for filling lines (morebeer.com). Small breweries commonly use bright tanks with stones; larger plants integrate in‑line skids so beer arrives at packaging on target.

Style setpoints and process losses

Brewers tailor CO₂ by style as a quality driver — ales ~2.2–2.7 volumes, lagers/light beers 2.5–3.0 volumes (mebak.org; morebeer.com). A practical rule of thumb used in manometric charts: 1 volume ≈2 g/L at ~20 °C. Since bottling can shed ~0.2 volumes and kegging ~0.05, setting slightly high in the bright tank is standard (morebeer.com). Even small gauge errors (e.g., 0.5 psi) can move beer by ~0.05 volumes — noticeable in glass (morebeer.com).

Measuring dissolved CO₂ accurately

The category standard is the Zahm & Nagel CO₂ volume meter (e.g., SS‑60): a manometric device that samples beer from a sealed tank, is shaken to equilibrate pressure and temperature, then read via a chart (ASBC BAM‑S10 method; Zahm & Nagel). Using Henry’s law — often via built‑in Haffmans equations (mebak.org) — those readings convert to volumes (again, 1 volume ≈2 g/L at ~20 °C). Zahm reports the SS‑60 “greatly improves accuracy and time” over older models via a precise piston and calibrated gauge (Zahm & Nagel), and labs regularly calibrate gauges (e.g., with a dead‑weight tester) to avoid drift (Zahm & Nagel). Miscalibration can misstate CO₂ by ~0.05 volumes even with good technique (morebeer.com).

To isolate “true” dissolved CO₂, laboratories also often absorb CO₂ chemically (KOH) and account for residual air (O₂/N₂) in the sample (mebak.org; mebak.org). As one brew lab guide emphasizes, pressure/headspace charts are approximate; instruments like Zahm’s or optical analyzers deliver “a much higher degree of accuracy,” and relying on regulator settings alone is “crude and often unreliable” (morebeer.com; morebeer.com).

Digital analyzers and in‑line sensors

Portable meters like Anton Paar’s CarboQC measure dissolved CO₂ directly in 2–6 minutes from small samples (~100–150 mL), differentiating CO₂ from other gases and logging 500+ results (Anton Paar; Anton Paar; Anton Paar; Anton Paar). The device reaches up to ~20 g/L (10 volumes) at low temperature with high precision (±0.005 vol).

For continuous control, in‑line CO₂ sensors (Anton Paar Carbo 5100/6100/6300) provide real‑time readings every few seconds in sanitary, EHEDG‑certified designs that typically need minimal maintenance. They also detect dissolved nitrogen and can be tied into closed‑loop carbonators (Anton Paar). Modern units cite a ~4‑second response and once‑a‑year cleaning (Anton Paar).

Carbonation equipment market context

Market demand for carbonation machinery — from compact in‑line systems to multi‑function skids that add deaeration — is rising worldwide. One report pegs the beverage carbonation‑equipment market at ~$4.2 billion in 2024, growing ~6.5% annually to ~$6.8 billion by 2033, buoyed by growth in emerging markets and craft brewers’ drive for consistency (linkedin.com; linkedin.com; mordorintelligence.com).

Troubleshooting common carbonation faults

Flat beer (undercarbonation) starts with verification: measure tank head pressure and beer temperature, estimate expected volumes (e.g., 13 psi at 4.5 °C ≈2.5 vol), then confirm with a meter (Zahm or CarboQC) (morebeer.com). Low readings usually trace to inadequate pressure or time, leaks, or metering error. Check the stone size/function, hold time, regulators, and line integrity; recalibrate gauges, as 0.5 psi error can mean ~0.05 volumes off (morebeer.com). In naturally conditioned beer, flatness may also reflect low priming or overly cold conditioning suppressing yeast activity.

Overcarbonation and “gushers” often reflect head pressure set too high for the beer’s temperature or equipment faults. Reset to style targets (e.g., pilsners ~2.5–2.8 vol; stouts ~1.5–2.0 vol). In package, foaming can also indicate microbial contamination; lab checks (microscopy, plating) and rigorous sanitation help. Residual protein/grease act as nucleation sites, so scrupulously clean bottles, cans, and taps.

Inconsistency batch‑to‑batch frequently points to miscalibrated instruments — verify thermometers and pressure gauges (dead‑weight testers are standard) (Zahm & Nagel). On tank stones, insufficient recirculation can stratify CO₂; on in‑line systems, confirm CO₂ flow calibration. Temperature uniformity matters; warmer beer holds less CO₂, so a warm batch with a “cold” gauge setting will under‑carbonate.

Excess foam in draft service despite correct tank CO₂ often traces to warm lines, mismatched line length/pressure, or dirty lines. Standard ratios (e.g., 5–7 psi per foot of ¼″ line at 38 °F) must match the beer style; too‑low operating pressure can paradoxically increase foam by flashing CO₂ early (shunbeer.com).

Packaging headspace issues have clear signatures: bulging cans or venting kegs indicate pre‑pack CO₂ was too high; soft pours imply insufficient CO₂ or gas loss from leaking seals. Confirm with in‑package CO₂ measurements (Zahm off a can or a CarboQC sample). Gas purity also matters: beverage‑grade CO₂ must be pure, and any O₂ in the gas line can cause off‑flavors and strip CO₂. Purge lines of air before pressurizing and use oxygen analyzers or dissolved O₂ meters as needed; nitrogen blanketing and oxygen scavengers are used where rejuvenation is a concern.

Across scenarios, the first step is accurate measurement. As brewing standards note, instruments like the Zahm meter or optical analyzers verify actual CO₂ levels; regulator charts are approximate (morebeer.com). Commercial filling typically drops CO₂ by ~0.2 vol in bottling and ~0.05 in kegging (morebeer.com), which brewers account for. Keeping records — e.g., CarboQC data logs or brewing software — of temperature, pressure, and measured CO₂ helps pinpoint drift: steadily rising head pressure needs to reach the same volume implies leaks or fading regulators; batch‑wise shifts often indicate process changes.

Specialized equipment snapshots

Zahm & Nagel CO₂ Volume Meter (SS‑60): a stainless piston‑based cylinder for manometric CO₂ measurement on bulk tanks. Operators set counterpressure, fill, shake to equilibrium, and read the chart (per ASBC BAM‑S10; Zahm & Nagel). Zahm says the SS‑60 “greatly improves accuracy and time” vs. older models (Zahm & Nagel); periodic gauge calibration (e.g., series‑8000 dead‑weight tester) is recommended (Zahm & Nagel).

Anton Paar CarboQC: a portable, optical/infrared dissolved CO₂ meter that delivers results in 2–6 minutes from ~100–150 mL samples, differentiates CO₂ from other gases (“true CO₂”), and logs 500+ measurements via USB/AP Connect (Anton Paar; Anton Paar; Anton Paar). It measures up to ~20 g/L (10 volumes) at low temperature with ±0.005 vol precision.

In‑line CO₂ sensors (Anton Paar Carbo 5100/6100/6300): sanitary, EHEDG‑certified sensors installed on pipelines/tanks for continuous CO₂ measurement, reporting values every few seconds with ~4‑second response and minimal upkeep (often once‑a‑year cleaning). They detect dissolved nitrogen and enable closed‑loop process control (Anton Paar).

Regulatory context in Indonesia

Indonesia’s BPOM recognizes carbon dioxide (E290) as a permitted additive in foods and beverages, and JECFA’s ADI (“acceptable daily intake”) is “not specified” — indicating no health‑based ceiling (antaranews.com; antaranews.com). National SNI standards for soft drinks (“limun”) specify 6–15% sugar and carbonation pressure of 20–70 psi — i.e., ≈1.4–4.8 bar (scribd.com). Beer has its own SNI (alcohol and hygiene), and producers align with labeling and sanitary expectations.

Operational checklist for fast fixes

- Verify targets vs. actual: measure tank/keg CO₂ and compare to design targets, factoring typical losses (~0.2 vol in bottling; ~0.05 vol in kegging) (morebeer.com).

- Check instrument calibration: confirm pressure gauges/thermometers; a 0.5 psi offset can mean ~0.05 volumes error. Calibrate Zahm meters and in‑line sensors per guidance (morebeer.com; Zahm & Nagel).

- Inspect equipment: look for tank/line leaks, loose fittings, faulty check valves; ensure stones are clean and not biofouled. On in‑line systems, confirm venturis/pumps and check for unintended CO₂ bleed‑off.

- Adjust process conditions: raise pressure or chill beer to increase solubility; to correct over‑carb, purge gently or warm to allow off‑gassing before packaging. Nitrogen purges help flush headspace when needed.

- Assess beer quality: low CO₂ can accentuate staling; CO₂ in solution buffers acidity and preserves aroma (mebak.org).

- Plan for supply risks: CO₂ shortages happen. Breweries are installing CO₂ capture to recycle fermentation gas (e.g., reported systems at Big Storm Brewing), and others are seeking to reduce CO₂ usage (axios.com; axios.com).

Breweries also keep an eye on where in the line to inject gas. In‑line carbonators often sit between a membrane filtration step and bright tanks or right before packaging (beerandbrewing.com), and modern skids meter flow and pressure on the fly. As multiple guides conclude, consistent, measured carbonation is “crucial for meeting consumer expectations,” and it’s best achieved with the right tools (linkedin.com; morebeer.com).