Ammonia converters run at 150–300 bar and 400–500 °C, a regime that rewards creep‑resistant alloys and punishes the wrong weld. Materials choices here can make or break multi‑decade reliability, especially under hydrogen embrittlement and nitriding risk.

Industry: Fertilizer_(Ammonia_&_Urea) | Process: Ammonia_Synthesis_Loop

In the ammonia synthesis loop, metals live hard lives. Modern converters sit in hydrogen‑rich H₂/N₂/NH₃ mixtures at 150–300 bar and 400–500 °C; that combination makes creep (time‑dependent deformation at high temperature) and hydrogen damage the dominant threats (pdfcoffee.com). Pressure shells are therefore built from creep‑resistant Cr–Mo steels such as ASME SA‑387 Grade 22 (2.25Cr–1Mo) or higher‑chromium martensitic variants like P91 (9Cr–1Mo‑V), which carry much higher allowable stresses at temperature than plain carbon steels. In fact, 9–12%Cr steels retain tens of MPa of creep strength at ~550 °C—roughly double that of 1–2%Cr steels at the same temperature (researchgate.net).

Converter internals are a different story. Here, austenitic stainless and Ni‑based alloys—SS304/316, 321, 330, Alloy 800—are favored because they retain toughness in hydrogen and resist high‑temperature hydrogen attack (HTHA), a microstructural decarburization and cracking mechanism in steels exposed to hot hydrogen (bcinsight.crugroup.com) (researchgate.net). Cold‑wall converter designs go further: by flushing cool inlet gas along the shell and confining the hot reaction to an internal cartridge of heat‑resistant material, they keep the ferritic shell at ~300–330 °C—below the HTHA danger zone (bcinsight.crugroup.com) (bcinsight.crugroup.com).

Converter shell and internals

For the pressure shell, low‑alloy Cr–Mo steels dominate—typically 2.25Cr–1Mo (SA‑387 Gr22) or upgraded Cr–Mo–V—because they resist creep (enabling thinner walls) and are allowed up to ~545 °C in codes. But they can suffer HTHA if exposed to hot H₂/NH₃. Experience matters here: in a BASF case, a 2.25Cr–1Mo converter developed cracking after only ~8 years, with nitriding and HTHA combining at welds under stress (pdfcoffee.com) (pdfcoffee.com). Design responses include minimizing shell temperature and weld stress.

Internals (grids, baskets, supports) lean austenitic: SS304L, 316L, 321, 330, or Alloy 800 (Ni–Fe–Cr). These are “not affected by HTHA” in converter service, per Casale’s analysis (bcinsight.crugroup.com). The trade‑off is nitriding: at high temperature, ammonia decomposes and nitrogen hardens stainless surfaces; designers optimize nickel content and thickness accordingly, and may specify Ni‑alloy overlays on critical parts (bcinsight.crugroup.com) (bcinsight.crugroup.com).

Metallurgy has moved the goalposts. Reviews note that tailored stainless and duplex grades can “improve high‑temperature creep‑rupture resistance,” effectively doubling or tripling creep strength versus older grades (researchgate.net). Practically, modern converters run 20–25 years between overhauls; early hot‑wall carbon steel designs failed in under 10 years.

High‑pressure piping alloys

The loop’s piping must be hydrogen‑compatible more than creep‑critical, and the industry trend favors austenitic stainless or nickel‑alloys in high‑pressure hydrogen service (epcland.com). Austenitic stainless steels (SUS304L, 316L, 321H), used in fully annealed condition to avoid hard microstructures, show strong resistance to hydrogen embrittlement at cool‑to‑moderate temperatures. ASME B31.12 (hydrogen piping) explicitly “focuses on materials that resist hydrogen embrittlement, such as austenitic stainless steel and certain nickel‑based alloys” (epcland.com). In practice, many ammonia plants run 316L or 321 on 100–300 bar lines, while controlling risk of hydrogen stress cracking (especially with moisture or stress) by limiting hardness (e.g., HRC ≤ 22) and rigorously inspecting welds.

Nickel‑based alloys—Incoloy 825, Alloy 625, Alloy 800—cover the highest‑duty circuits or cramped layouts. They resist hydrogen better than steels and are immune to HTHA even above 500 °C, enabling higher temperature/pressure at a given wall thickness. The drawback is cost: typically 2–5× carbon steel. Designers balance capital vs. longevity when specifying these materials.

Ferritic Cr–Mo steels still appear outside the hottest zones: 1.25–2.25Cr–Mo grades are used where gas is cool and hydrogen partial pressure is limited. P22 (2.25Cr–1Mo) remains common in manifolds or hot gas lines, but only where outlet temperature stays below ~400 °C (researchgate.net). Temperature spikes as small as +50 °C can slash allowable life by orders of magnitude—e.g., from 100,000 h to ~1–2 years—in overheating studies (researchgate.net).

Because of the pressure, loop piping uses heavier‑wall grades than general service. ASME B31.3 allows SA335 P11/P22/P91 to defined temperatures, while ASME B31.12 (pure H₂) is even more restrictive. Many engineers treat synthesis piping as “hydrogen service,” adopting B31.12’s toughness and hardness practices. Regular pressure tests and hydrogen‑sensor leak detection align with these practices (epcland.com).

Hydrogen attack and nitriding mechanisms

HTHA (high‑temperature hydrogen attack) occurs when hydrogen diffuses into steel above roughly 400 °C and forms methane at carbides, causing decarburization, cracking, and blistering. In hot converter sections, this shows up in shells or heaters. The BASF case highlights the risk: 2.25Cr–1Mo converter welds cracked under the combined influence of nitriding and HTHA, forcing replacement after ~8 years (pdfcoffee.com) (pdfcoffee.com). Standard Nelson curves (empirical HTHA boundaries) may underestimate risk in ammonia because nitriding can concentrate hydrogen at welds (pdfcoffee.com). API 941 guidance and field experience therefore limit ferritic steels to “cold” zones (<350 °C) with low hydrogen partial pressure.

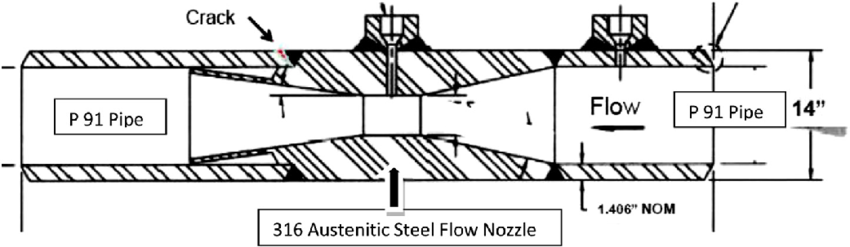

Low‑temperature hydrogen effects—often grouped as hydrogen embrittlement or hydrogen‑assisted cracking—can affect piping and welds at ambient to moderate temperatures. Austenitic steels and nickel alloys are almost immune; martensitic/ferritic steels need strict control. For example, strong 9%Cr steels like P91 can trap hydrogen in the heat‑affected zone if welding is not handled carefully. Junak et al. (2022) report multi‑pass P91 welds suffering ductility loss from absorbed hydrogen, especially in as‑welded (non‑tempered) condition (link.springer.com) (link.springer.com). Mitigation is procedural: preheat, slow cool (e.g., to ~80 °C), hydrogen removal bake, and PWHT (post‑weld heat treatment) at ~700 °C before service (link.springer.com). In hydrogen service, hardness limits (Brinell ≤197/≈HRC22) are enforced; designers often prefer austenitic pipe, bolted joints, or weld overlays in the most critical H₂ circuits.

Ammonia also drives nitriding—nitrogen diffusion that hardens and embrittles stainless—above roughly 450 °C. Cold‑wall design isolates the ferritic shell; internals are chosen for nickel content and thickness to manage nitriding rates (bcinsight.crugroup.com) (bcinsight.crugroup.com). Duplex or stabilized austenitic alloys (with Ti or Nb) help reduce nitride formation; internal parts often carry sacrificial corrosion allowance and are inspected at long intervals.

Material selection and reliability strategy

Several practices underpin long life in hydrogen:

- Use of resistant alloys: For hot/high‑pressure H₂, specify austenitic stainless or Ni‑alloys rather than carbon steel (epcland.com) (researchgate.net). Reviews note that adding Cr, Mo, Nb, W to stainless can roughly double creep life; duplex stainless steels (≈22Cr‑5Ni or higher) are used in heat exchangers or intermediate piping for strength with H₂ tolerance (researchgate.net).

- Design to limit exposure: Keep hydrogen above 400 °C off ferritic shells via cold‑wall designs, insulation, and rapid outlet cooling. Transient upsets matter: BASF observed that brief catalyst hot spots added tens of °C to shell temperature; redesigns focused on lowering weld stress (pdfcoffee.com) (pdfcoffee.com).

- Fabrication controls: Tight welding procedures are mandatory. Cr–Mo ferritics require full stress relief; martensitic steels need multi‑step preheat/dehydrogenation/PWHT sequences as in Junak et al. (link.springer.com). On piping, weld hardness must meet ASME B31.12 limits, with hydrogen bake‑outs (e.g., 300–400 °C holds) used on critical joints. After finding cracks, BASF NDT‑inspected all converter girth welds every 2.5 years (pdfcoffee.com) (pdfcoffee.com).

- Monitoring and inspection: Plants use crack‑growth models tied to inspection data (e.g., crack depth vs. operating hours) to set inspection intervals and safe removal times (pdfcoffee.com) (pdfcoffee.com). Continuous H₂ sensors and periodic leak tests align with hydrogen code practice (epcland.com).

- Compliance with standards: Indonesian plants follow SNI (national standards) mirroring ASME/ISO for pressure equipment. ASME B31.3 (chemical) and B31.12 (hydrogen) are commonly applied; Indonesian boiler/pressure vessel codes under MI&E echo these, requiring qualified materials and procedures for high‑pressure hydrogen. Vendors certify materials of construction (MOC) to SNI equivalents of ASTM/ASME.

These choices are economic as much as technical. Specifying nickel‑alloy piping can raise CAPEX by 20–50%, yet remove a major failure mode (hydrogen cracking) and tighten uptime. The calculus is stark: a single converter weld crack can trigger a months‑long shutdown (at album millions of $/day). Plants also keep hydrogen dry with oxygen scavengers—commercial options mirror boiler practice, such as oxygen scavengers—and rely on careful purging procedures and cathodic protections where applicable.

Source notes and further reading

Case histories and standards underpin this guidance. BASF reported 2.25Cr–1Mo converter weld cracking after ~8 years (pdfcoffee.com) (pdfcoffee.com). Converter design notes emphasize austenitic internals and cold‑wall shells to avoid H₂ damage (bcinsight.crugroup.com) (bcinsight.crugroup.com). ASME B31.12 highlights austenitic/Ni‑alloys for hydrogen piping (epcland.com). Reviews catalog gains from modern stainless/duplex metallurgy in ammonia service (researchgate.net). All information is drawn from up‑to‑date technical literature and standards.