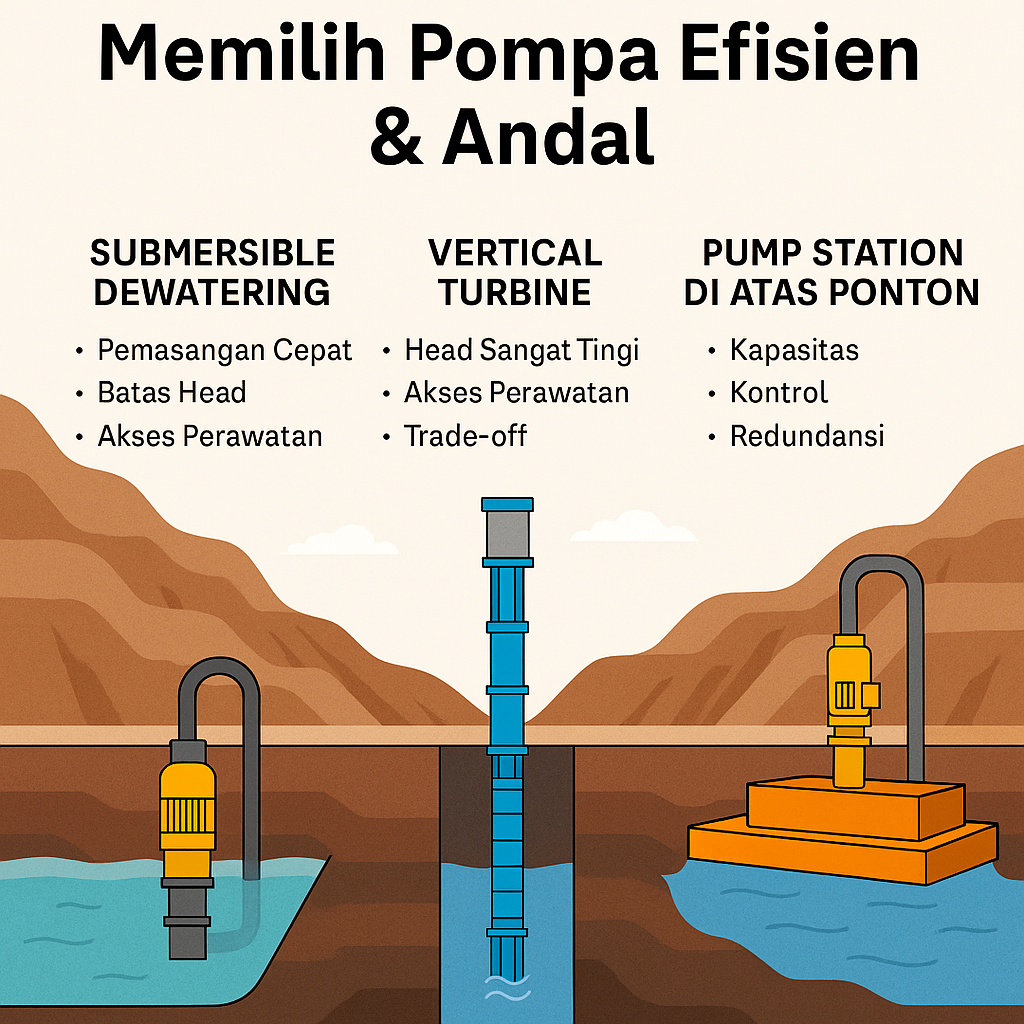

Coal mines live and die by dewatering. The choice between submersible, vertical turbine, and pontoon-mounted pumps decides whether operations ride out monsoons and high heads—or stall.

Industry: Coal_Mining | Process: Dewatering

In coal heartlands, a flooded pit is downtime and danger. In Indonesia’s East Kalimantan, coal contributed 33.8% of regional GDP during 2015–2019 (tandfonline.com), so the costs of dewatering failure are steep. Across mines, three pump setups dominate: submersible units in sumps, vertical turbine pumps for high heads, and pontoon-mounted stations for open water. The common design brief: handle variable inflows and high static heads with robust controls and redundancy (mdpi.com) (tandfonline.com).

Mining executives increasingly weigh lifecycle OPEX over sticker-price CAPEX; durable, efficient pumps paired with local service support are now the norm (im-mining.com) (im-mining.com).

Submersible pump deployments and limits

Submersible dewatering pumps—electric or hydraulic—sit underwater in sumps or flooded chambers; the motor is inside the casing, so priming is unnecessary and installation is straightforward (mdpi.com). They can be placed below the water surface and start immediately. Because they run submerged, the pumped fluid cools the motor.

There are real trade-offs. One industry source notes submersibles’ power and capacity are generally lower than above‑ground units (sewatama.com), and “electric submersible pumps can handle large volume or significant heads, albeit limited to smaller solids at higher heads” (sewatama.com). In practice, they cover large volumes at moderate to high head (head is the vertical lift against gravity), but solids-handling capacity tightens as head rises.

Evidence of reliability abounds. At Anglo American’s Minas‑Rio, more than 80 Sulzer submersible dewatering pumps have run continuously under rain catchments; they operated for 4 years without maintenance in abrasive conditions—helped by wear‑resistant components and modular designs (sulzer.com) (sulzer.com) (sulzer.com) (sulzer.com).

Operationally, submersibles suit underground sumps and open‑pit floor dewatering, with low surface footprint and no priming (mdpi.com). Maintenance requires lifting the unit out of the water, and while installation cost is often lower, poorly ruggedized designs can drive higher O&M than surface pumps (pumpsandsystems.com). Large mines closely track pump performance; where pumps fail, OPEX spikes quickly (im-mining.com). Many operators prefer high‑efficiency submersibles with local service support and spares on hand (sulzer.com) (sulzer.com).

Vertical turbine pump characteristics

Vertical turbine pumps (shaft‑driven, multistage centrifugal units) place intake screens below the waterline with the drive motor above water on a deck or pit rim (mg.aquaenergyexpo.com). Multiple impellers in series deliver very high head suitable for deep static lifts—heads of several hundred meters are achievable. They are “widely used for mine dewatering” for their compact footprint, high capacity, and flexibility (pumpsandsystems.com).

Applications include deep shafts, dewatering raises, and booster stations, including floating barge installations. They handle large flows—hundreds to thousands of L/s (liters per second)—and are often configured in multi‑stage, multi‑thousand‑L/s builds (pumpsandsystems.com).

Efficiency is a calling card: vertical turbines are generally more efficient than horizontal or submersible designs for water service. Installation is more complex (shaft alignment, foundations), but once running, maintenance access is easier with motors and couplings above water (mg.aquaenergyexpo.com) (pumpsandsystems.com).

Reliability has been proven in harsh environments. KSB’s “B” series vertical turbine pumps mounted on pontoons have delivered for decades in Brazilian mines (im-mining.com). Trillium highlights durability and smaller footprint compared to multiple horizontal pumps (pumpsandsystems.com). The trade‑off: higher CAPEX and installation effort (especially large motors on pontoons or deep wells), even though submersible vertical units can cost less to install—operators often evaluate this against lifecycle costs (pumpsandsystems.com).

Pontoon-mounted pumping stations

Floating pump pontoons (barges) dominate open‑pit lakes and tailings ponds. A buoyant deck supports one or more pumps and motors, anchored in the pit’s dewatering pond; the platform rises and falls with the water level, maintaining optimal intake depth and eliminating frequent suction‑line moves (im-mining.com).

Capacity is substantial. Pontoons can carry large pumps—often vertical turbines—and high‑power diesel or electric drives; KSB built pontoon stations in Brazilian mines that delivered required flows for decades (im-mining.com). Because the platform floats, pumping continues uninterrupted during heavy rain without manual repositioning, reducing labor and downtime and improving lifecycle costs (im-mining.com).

Limitations are practical: pontoons require open water and add complexity and cost (flotation, mooring, safety). Still, “after 20 successful years… [pontoon‑based pumping] has become the standard for this type of equipment in South America” (im-mining.com).

Dewatering system design parameters

Floods are seasonal, inflows are variable, and heads run high. Resilient systems build in redundancy, capacity, and controls. Redundancy typically follows an n+1 arrangement (n+1 means one extra pump beyond required capacity) so peak flow is met even if a unit is down, with two independent power sources—e.g., grid plus generator—and auto/manual switching between pumps to ensure continuity (mdpi.com) (mdpi.com).

Capacity should exceed the highest expected inflow (monsoon, dam release). Controls stage pumps on/off or apply variable‑speed drives as flows change, while monitoring flow rate, water level and quality; emergency manual overrides are standard for safety (mdpi.com).

Reliability hinges on robust metallurgy and proven designs for abrasive water (sulzer.com). As the industry shifts from low purchase price to long‑term OPEX, “poorly designed equipment that regularly fails” is recognized as a cost driver; mines prioritize high‑efficiency, reliable pumps with local service support (im-mining.com). Case in point: after reliability issues with earlier units, one owner switched to modern dewatering pumps with modular, wear‑resistant components; the pumps have run for years maintenance‑free, with a local service center stocking spares to cut downtime (sulzer.com) (sulzer.com).

Discharge water treatment and compliance

In coal mining, pumped water often needs treatment or neutralization before discharge. Indonesian rules (MoE PermenLHK No.4/2012) cap mining impacts on groundwater; coal activities “may not decrease the pH of groundwater by more than one level” (tandfonline.com). Designs commonly include settlement ponds, treatment plants or chemical dosing so discharge meets standards, with continuous pH and sediment monitoring integrated into control systems (mdpi.com).

Where chemical neutralization is applied, mines deploy precise metering via a dosing pump, supported by site‑specific controls and water‑treatment ancillaries that integrate with the dewatering PLC and instrumentation.

Selection and lifecycle outcomes

Choice tracks geology and hydrology: submersibles are quick to install and fit sumps; vertical turbines dominate deep lifts and long hauls; pontoons suit large, fluctuating open water. Across all types, systems are sized and duplicated—redundant pumps and power—to meet peak inflows without interrupting production (mdpi.com) (im-mining.com). Data‑driven selection—capacity, head, lifecycle cost—keeps pits dry and mining operations safe and uninterrupted.

Sources: Industrial and research literature on mine dewatering and pump reliability (mdpi.com) (im-mining.com) (im-mining.com) (mdpi.com) reports on equipment performance; Indonesian regulatory analyses (tandfonline.com) (tandfonline.com); and case studies of pump installations (sulzer.com) (sulzer.com). All figures and citations provided are from these sources.