From abrasive “dirty water” to toxic metals, dewatering is now a 24/7 engineering project, not a cost center. Mine planners are sizing pumps and plants for monsoons, not averages — and building treatment lines that can hit stringent discharge limits.

Industry: Coal_Mining | Process: Extraction

Coal operations routinely move thousands of cubic meters per day to keep pits and underground headings dry. One Botswana open‑pit site ran a Sykes diesel unit to remove about 103 million liters in 30 days — roughly 3,400 m³/day — according to industry reporting (E&MJ). As mines go deeper and tropical monsoon rains intensify, dewatering is becoming increasingly necessary (E&MJ).

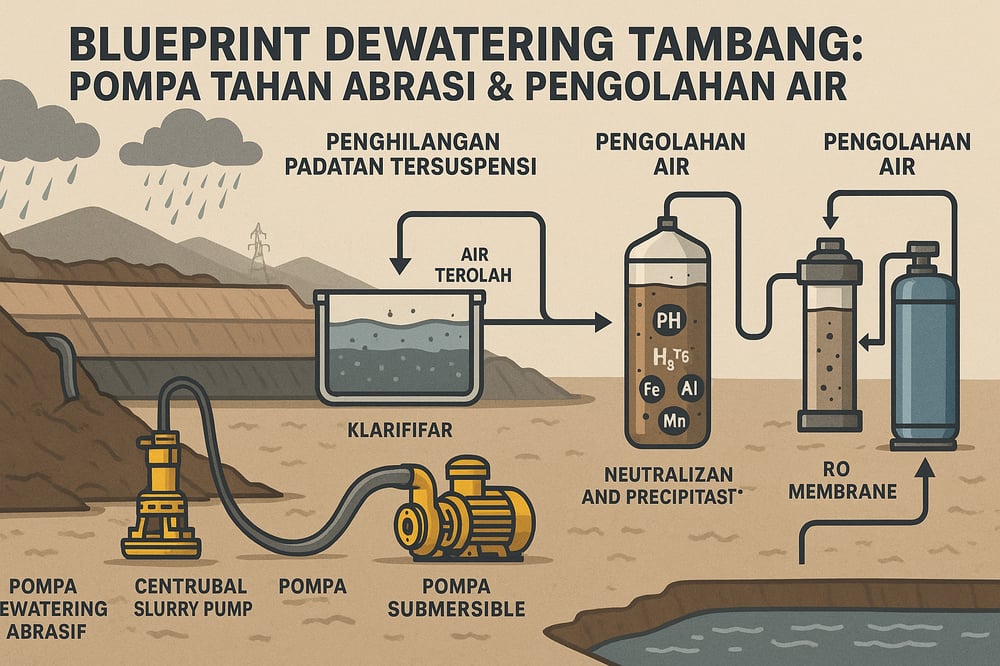

The incoming water isn’t clean. Irrigating groundwater and storm runoff into pits produces “dirty water” loaded with suspended sediment and fines that erode pump internals (E&MJ). Sudden events — heavy rains, landslides, a failed settling pond — can spike solids or acidity, creating “upset” conditions that both pumps and treatment must tolerate (E&MJ). Without treatment, pumped mine water can carry low pH and toxic metals (iron, aluminum, manganese) well above environmental standards (Heliyon/PMC) (GreenChem Indonesia).

Regulators set the floor. Indonesian Mine Wastewater Standards (KepMen LH 113/2003) specify pH 6–9 and caps of 7 mg/L Fe, 4 mg/L Mn, and 400 mg/L TSS (total suspended solids) (GreenChem Indonesia). Western guidelines are often tighter — for example, U.S. coal‑mining effluent limits of TSS ≤70 mg/L, Fe ≤7 mg/L, Mn ≤4 mg/L (MDPI). In practice, many planners design for even more stringent effluent, such as TSS <30 mg/L, to create buffer against upsets.

Industry thinking has shifted as well: sustainable water reuse, digital monitoring, and tailored site designs now shape dewatering programs (E&MJ) (E&MJ), rather than treating dewatering as a neglected cost center (E&MJ).

Abrasion‑resistant dewatering pumps

Submersible and centrifugal units built for mines lean on hard‑metal or thick rubber liners and high‑chrome impellers to survive abrasive flows (E&MJ) (E&MJ). Xylem’s Flygt 2600‑series dewatering pumps, for instance, use specially hardened, closed impellers (E&MJ), while high‑solids duties point to specialized slurry pumps such as Weir’s Warman DWU (E&MJ).

Intake hygiene matters: washing and coarse screening keep large debris out; many sites rely on intake screens analogous to a manual screen, and some pumps add snowplow‑style cutters or mixers. As one expert put it, “the introduction of… abrasive suspended solids is one of the most common causes of premature failure in a dewatering pump” (E&MJ).

Capacity spans from a few hundred to several thousand m³/hour for mine dewatering; by contrast, large mill‑circuit slurry pumps can exceed 14,000 m³/h with 4,000 kW motors (E&MJ) — dewatering units for groundwater are often smaller. Designs commonly feature duty/standby redundancy and VFDs (variable‑frequency drives) to follow inflow fluctuations. Getting this right is site‑specific: engineers “must understand the water inflow requirements, how that impacts the mine plan [and] range of operating depths,” and match equipment to existing pipework (E&MJ).

Oversizing has been common historically and wastes energy; modern practice is to right‑size pumps, often with VFD control, for best efficiency (E&MJ). Remote telemetry flags vibration or power‑draw changes, enabling preemptive maintenance — because if a pump does fail, replacement is often the only option (E&MJ).

Clarification and solids management

The first treatment step is solids removal. Sites deploy settling units or ponds, dosing coagulants/flocculants (coagulants bind fine particles; flocculants help those larger clusters settle) such as polyacrylamides or alum (MDPI). Many plants use a dedicated clarifier to create residence time; U.S. coal‑prep effluent rules assume coag/floc to reach TSS ≤70 mg/L (MDPI).

Retention times of several hours — up to ~24 hours in large ponds — are typical. Chemistry is tuned with agents like coagulants, flocculants, and, as applicable, aluminum salts such as PAC. Many mines also use geotextile flow‑through containers (geotube bags) to dewater sludge: at a South Kalimantan coal operation, engineers pumped to 300 large geotubes and dewatered about 1,000,000 m³ of pond sediment per year (~170,000 m³ dry solids), freeing capacity (Solmax).

For very low residual turbidity targets, pressurized media and cartridge polishing is added — for example, sand media via sand/silica filtration, followed by cartridge filters when required.

Neutralization and metal precipitation

Dissolved contaminants — notably Fe, Al, Mn, Zn — are handled by chemical precipitation. In a neutralization tank, lime (Ca(OH)₂) or caustic raises pH into the 8–11 range, and aeration oxidizes Fe²⁺ to Fe³⁺ to improve removal (Heliyon/PMC). Ferric iron begins to precipitate around pH ~3.5, whereas Mn and Zn require near‑neutral pH of 6–9 (Heliyon/PMC).

Extensive studies show chemical precipitation removes more than 95% of common toxic metals, though it produces voluminous “yellow boy” hydroxide sludge (Heliyon/PMC). Advanced seeded‑precipitation designs (e.g., SPARRO®) use controlled pH and crystal nuclei to manage scale and maximize recovery — but still rely on precipitation as the primary mechanism (Heliyon/PMC). These steps consume reagents and demand careful sludge disposal; plants often source their reagents as part of a water and wastewater chemicals program.

Membrane or adsorbent polishing

Where very low metals or TDS (total dissolved solids) are required, membranes or adsorbents finish the job. Reverse osmosis (RO — a pressure‑driven membrane separation) has been used in pilot systems to achieve drinking‑water quality after precipitation (Heliyon/PMC), typically via a brackish‑water RO configuration within broader membrane systems.

Carbon or ion‑exchange resins can also remove trace heavy metals at higher operating cost, which aligns with the use of activated carbon or targeted ion‑exchange resins in polishing service.

Compliance targets and monitoring

Effluent is monitored continuously. Inline sensors for pH, turbidity (as a proxy for TSS), and conductivity (as a proxy for dissolved salts) feed control of alkali dosing; labs validate metals (Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn) and acidity. Discharge occurs only after all permit criteria are met, including Indonesia’s pH 6–9 and the Fe/Mn/TSS caps noted above (GreenChem Indonesia). Many operators aim to beat those limits with a safety margin — for example, targeting pH ~7–8, Fe <2 mg/L, TSS <50 mg/L.

Planning, energy, and operating costs

Integration is non‑negotiable: dewatering capacity and treatment throughput must be sized for peak wet‑season loads, not averages. Operations run around the clock; a missed pump or clogged clarifier can halt production. On the upside, modern designs emphasize reuse — treated mine water is often recycled for dust control or wash plants (Heliyon/PMC) — and electrified, automated controls have improved energy efficiency by tracking inflow curves (E&MJ).

Costs can be high. Strongly acidic drainage can require tens of tons of lime per day; high solids translate into frequent maintenance, with offline time for pump rebuilds or filter changes expected. A long‑running Indiana project (Alliance Coal) found that a specialized slurry pump could extend operational life versus a standard dewatering unit. In South Kalimantan, integrated dewatering and sludge management — including the 300‑geotube campaign processing ~1,000,000 m³ of sediment (~170,000 m³ solids) — restored pond capacity and enabled recycle of clarified water to the wash plant (Solmax).

Across programs, the end goal is zero discharge excursions. With proper sizing of pumps and treatment lines, effluent can be consistently discharged within Indonesian and international standards (GreenChem Indonesia) (MDPI).

Key design takeaways

- Plan dewatering and treatment together. Model inflows and contaminant loads early, and build enough pump and clarification capacity into the mine plan (E&MJ) (E&MJ).

- Choose abrasion‑resistant equipment. Submersible and surface pumps with hardened parts (rubber‑lined pumps or high‑chrome impellers) minimize wear (E&MJ) (E&MJ).

- Meet or exceed standards. Design to achieve effluent below the strictest applicable limits (e.g., pH 7–8, Fe ≪7 mg/L, TSS ≪70 mg/L) as a buffer against upset conditions (GreenChem Indonesia) (MDPI).

- Allow flexibility and monitoring. Multiple pumps and real‑time sensors help operators respond to spikes in water or solids, preventing overload.

- Consider life‑cycle costs. Rugged pumps and complete treatment trains cost more upfront but pay back in uptime and environmental compliance.

References underpinning the figures and practices above include E&MJ engineering features (E&MJ) (E&MJ), environmental reviews (Heliyon/PMC) (MDPI) (Heliyon/PMC), and Indonesian regulations (KepMen LH 113/2003) cited via GreenChem Indonesia and Nawasis.