High‑density sludge (HDS) treatment is shrinking acid mine drainage waste by up to ~90% and setting up dewatering and metal recovery wins. Filter presses and geotextile tubes split the work; selective chemistry pulls Cu, Zn, Ni, and even magnetite back out.

Industry: Coal_Mining | Process: Acid_Mine_Drainage_(AMD)_Prevention_&_Treatment

Coal mines don’t just pump water; they pump liabilities. Acid mine drainage (AMD, acidic water that leaches metals and sulfate from rock) leaves behind tons of sludge after neutralization. The shift to high‑density sludge (HDS, a process that recycles precipitated solids as “seed” to capture more metals and sulfate) is changing the math.

In one U.S. case, converting a conventional system to DenseSludge (a Veolia HDS variant) cut sludge volumes by ~90% and produced cakes up to ~70% solids (coalage.com). Typical HDS sludge runs 15–70% dry solids with bulk density 1050–1370 kg/m³ versus only ~5% in conventional lime/dracor procedures (mdpi.com), which translates to drastically less water in the filter cake and faster handling.

Scale that to coalfield reality and the tonnage adds up. Sukati et al. estimate ~20 ton dry HDS per megaliter (ML) of AMD treated; at a predicted 360 ML/day flow (as in the Mpumalanga coalfields) that’s ~7,200 ton HDS/day (mdpi.com). The concentrated nature of HDS (with nickel, manganese, etc.) can push it into hazardous categories under some regulations (mdpi.com), but the smaller volume and higher density ease disposal and handling.

High‑density sludge (HDS) recycling

HDS systems recycle precipitated solids back into the reaction tanks, promoting further metal and sulfate removal on particle surfaces. That seed bed makes the particles settle much faster and pack more tightly (coalage.com), an advantage for downstream settling equipment such as a clarifier that removes suspended solids with 0.5–4 hour detention time.

Operators also report lower reagent usage and less scaling when recycling sludge to neutralization. Moon et al. (2011) describe how DenseSludge‑style feeding (lime into recycled sludge rather than raw AMD) allows precipitation at a slightly lower pH setpoint, saving alkali; they note not only ~90% sludge reduction but also much drier cakes with much less retained water (coalage.com). Plants that step pH carefully often use accurate chemical dosing; a dosing pump provides controlled alkali feed during these pH adjustments.

In effect, each ton of AMD neutralized in an HDS plant produces far less wet sludge than conventional (often called low‑density sludge, LDS) treatment. Sukati et al. report HDS solids at 15–70% dry solids (bulk density 1050–1370 kg/m³) versus ~5% for conventional lime/dracor approaches (mdpi.com), while DenseSludge implementations routinely post ~90% volume cuts (coalage.com).

Dewatering technologies and throughput

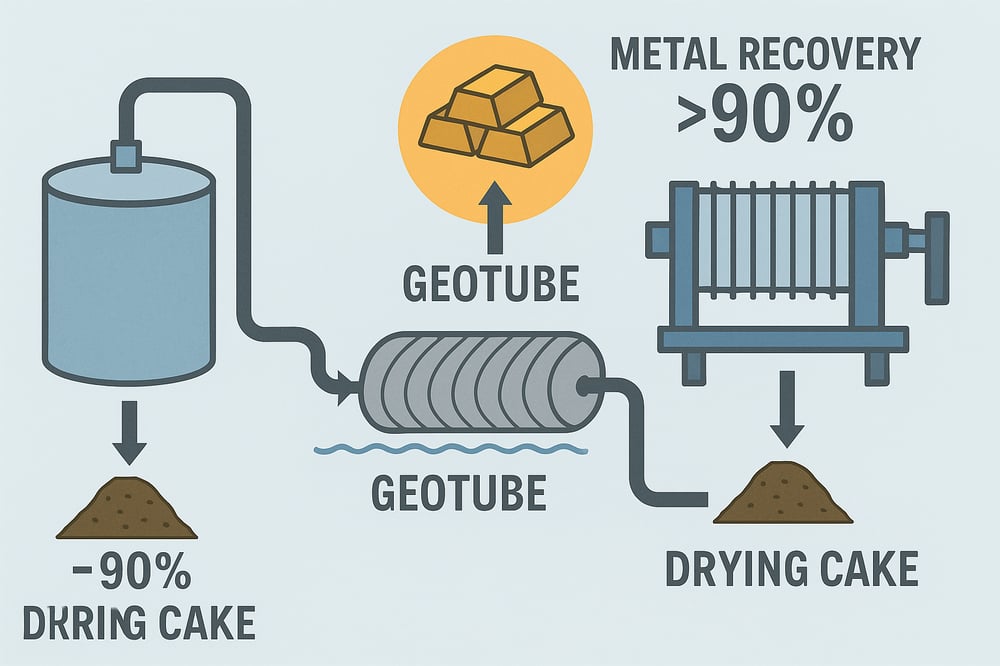

After precipitation, AMD sludge must be dewatered. Filter presses (plate‑and‑frame or membrane types; membrane presses add a squeezing step) are common for high‑solids recovery and can produce very high cake dryness—often 50–70% solids depending on feed chemistry and pressure (mse-filterpressen.com). MSE Filterpressen notes membrane presses yield higher residual solids and cut cycle time by dramatically increasing cake DM (dry mass) via squeezing (mse-filterpressen.com).

In practice, belt or chamber presses in mining often achieve on the order of 30–60% cake solids. Advantages: mature, fast, and they yield nearly drip‑free cake. Drawbacks: capital‑ and labor‑intensive (many moving parts, filter cloth cleaning, skilled operation), with limited throughput; a modern filter press may handle a few hundred L/min and requires pumping power, with maintenance and cloth replacement adding cost.

Geotextile dewatering (geotubes) is the gravity‑based, large‑volume alternative. Slurry—often flocculated—is pumped into woven tubes that hold solids as water seeps out. Bishop Water reports geotube systems pumping AMD slurries at ~2,000 gpm (7,600 L/min), far exceeding published belt‑press rates (~150 gpm for portable units) (bishopwater.ca). Because geotubes are passive, capital and energy costs are low (no mechanical press, little electricity); operation is simpler—once set up with polymer feed, the system largely runs itself (bishopwater.ca). Plants commonly pair geotubes with polymers; a flocculant improves particle aggregation and capture efficiency.

Performance is steady: solids capture can exceed 90–95% of suspended solids (bishopwater.ca), with initial dryness ~18–20% (similar to a belt press) (bishopwater.ca). Leave the tubes in place and gravity keeps working: Cincinnati tests showed coal‑fine geotube cakes reaching >55% solids after 4–6 weeks (tencategeo.asia), and a waste‑wine case pushed biosolids from 20% up to 30–35% solids by leaving them longer (tencategeo.asia). Downsides: large footprint; weather‑ and time‑dependent dewatering; residual cake still moist (25–55% solids) needing landfill or reuse; fine particles can clog fabric if chemistry is poor.

Typical performance ranges (for comparison)

- Filter Press: Cake solids ~50–70% (higher with membranes), filtrate very clear, batch cycles of hours, handles <500 L/min per unit, high capex/opex.

- Belt Filter: Cake solids ~30–50%, continuous flow moderately high (100–300 L/min), cheaper than filter press but lower dryness, cloth tensioning needed.

- Geotube: Cake solids ~30% initially (can reach 50%+ with time), continuous pumping at very high flow (1000+ L/min per train), very low capex, minimal energy.

(See also NihaoWater† for belt/screw press comparisons and MSE/Metso for tailored mining presses.)

Selective metal recovery routes

AMD sludges can contain recoverable metals. Typical AMD contains iron, aluminum, manganese, plus trace Cu, Zn, Ni; many authors note “AMD streams contain valuable metals (Zn, Cu, Ni, etc.)” (researchgate.net). With targeted chemistry, a high fraction can be harvested instead of landfilled.

Sequential precipitation: by raising pH in steps, specific metal hydroxides/carbonates can be precipitated selectively. Park et al. (2013) found adjusting AMD to pH ~7–9 allowed sequential Cu and Zn hydroxide precipitation. Reported recoveries: ~91% Zn and ~94% Cu in a mixed Cu–Zn stream, and ~94% Ni/95% Cu in a Cu–Ni stream (researchgate.net). In practice, co‑precipitation must be avoided; Zn and Ni are chemically similar, requiring careful separation.

Macingova et al. (2012) used a two‑stage “selective sequential precipitation” (first remove Fe/Al, then others with OH⁻ or biogenic H₂S) and achieved >99% removal of Cu and Zn (as sulfides from H₂S) and similarly high Fe/Al removal at controlled pH (researchgate.net).

Solvent extraction/ionic liquids: Caporali et al. (2022) studied an AMD (initial ~53 g/L Fe, 2 g/L Zn) and used a custom ionic liquid (AliCy) to extract Fe(III) preferentially. A two‑step process—extract Fe then biogenic sulfide precipitation of Zn—removed ~92% Fe and allowed ~85% Zn to be recovered as fine ZnS particles (link.springer.com).

Magnetite production: instead of letting Fe(II) oxidize to amorphous hydroxide, iron can be steered to magnetite (Fe₃O₄). Rapeta et al. (2023) show that dosing a mix of Fe³⁺ and alkali enables Fe²⁺ to co‑precipitate as Fe₃O₄ (via Fe(OH)₂ + Fe(OH)₃ → Fe₃O₄). The resulting magnetite‑rich sludge settles very quickly and can be separated magnetically; magnetite is a valuable iron ore used in heavy‑media separation or as pigment (mdpi.com).

Other routes include acidic leaching of dewatered sludge (e.g., sulfuric acid) for traditional hydrometallurgy (e.g., Zn electrowinning), and thermal/pyrometallurgy. In Indonesia, for example, high Fe sludge could potentially be used as iron‑rich filler or for pigment. Carbonization (biochar) of sludge has been explored to immobilize or recover certain elements. All depend on sludge composition: for coal AMD sludge the main “resource” is usually iron (and sometimes Mn or trace metals), whereas metal sulfide mines’ sludges may contain appreciable Cu, Zn, Ni, etc.

Data points, economics, and sources

Data/Trends: HDS dramatically raises sludge solids (to 30–70%). DenseSludge implementations routinely report ~90% sludge volume reduction (coalage.com). Filter presses can achieve cakes >50% solids (with membrane squeeze; mse-filterpressen.com) but require high energy per tonne. Geotubes capture ~95%+ solids (bishopwater.ca) and can drain large volumes, often reaching ~25–55% solids over time (tencategeo.asia) (bishopwater.ca). For metal recovery, case studies show >90% heavy‑metal yields (Cu, Zn, Ni) via controlled precipitation (researchgate.net) (researchgate.net), and Fe can be valorized as magnetite (mdpi.com). These outcomes are broadly confirmed in peer literature, making HDS + efficient dewatering + targeted recovery a promising best‑practice for AMD sludge management.

An often‑overlooked upside: integrating metal recovery (especially on large AMD projects) could offset treatment costs and turn waste into a product. Sludge disposal costs can be high—often tens to hundreds of USD per tonne, especially if classified hazardous. Even moderate metal grades (e.g., 0.1–0.5% Zn in sludge) could be worthwhile at scale (researchgate.net) (researchgate.net) (link.springer.com).

Sources: The above figures and trends are drawn from peer‑reviewed studies and industry reports (mdpi.com) (coalage.com) (tencategeo.asia) (bishopwater.ca) (researchgate.net) (researchgate.net) (link.springer.com) (mdpi.com), along with technical literature from filter‑press and geotube vendors (mse-filterpressen.com) (bishopwater.ca).