Energy recovery devices can shave ~25–40% off seawater RO power (peak ~60%), but only if maintenance is as disciplined as the hydraulics. Here’s the plant-floor playbook—what to log, what to open, and what to replace—to keep pressure exchangers and turbines on song.

Industry: Desalination | Process: Energy_Recovery_Devices

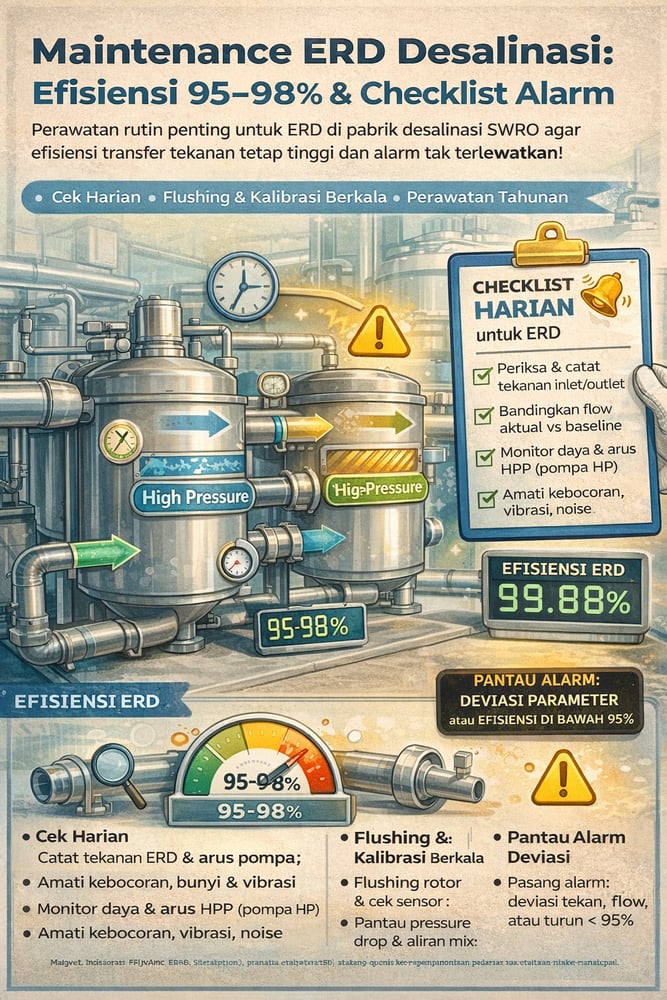

Modern isobaric energy recovery devices (ERDs)—notably pressure exchangers—are built for longevity and high efficiency, with manufacturers citing peak pressure‑transfer efficiencies near 95–98% (energyrecovery.com, www.frontiersin.org). Energy savings in seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) can reach ~25–40% versus no‑ERD baselines, with peak figures around ~60% (www.slideshare.net, www.frontiersin.org). In context: energy often accounts for 40–45% of SWRO water production cost (www.aesarabia.com).

Pressure exchangers (PX—an isobaric device that transfers pressure between brine and feed without a turbine) are designed for decades of service—on the order of ~~30 years~~ in fatigue-life analyses—with reported ~99.8% availability and effectively “no wear parts” (no pistons, no valves), so OEMs note they “require no routine maintenance” (energyrecovery.com, energyrecovery.com). In practice, routine inspection—rather than frequent overhaul—keeps them at spec (www.tidjma.tn, energyrecovery.com).

For plant teams running sea‑water RO systems alongside ERDs, this is the maintenance and troubleshooting guide—built from manufacturer data and technical reviews—with all numbers, side notes, and reference URLs included as cited below.

Pressure exchanger routine inspection

Daily/weekly practice centers on reconciling instruments to the commissioning baseline. Typical checks include: high‑pressure (HP) inlet/outlet readings, concentrate flow versus design, and high‑pressure pump (HPP) power draw. Slight rises in HPP current or reductions in permeate flow often indicate ERD performance loss. Visuals matter: the casing and piping are inspected for leaks, air entrainment (air can cause noise and pressure pulsations—“bleed air” is a standard remedy: www.manualslib.com), or unusual vibration. PX housing integrity (no cracks, tight flange bolts) is confirmed, and orientation marks are verified; the rotor end marked “HPIN” must face the high‑pressure inlet—backward installation is associated with noisy, poor operation (www.manualslib.com). In practice, after any service, teams verify that the “Concentrate” side of the cartridge faces the brine stream (www.manualslib.com).

Pretreatment upstream of the RO helps avoid confounding alarms—surface-water solids are typically handled with ultrafiltration pretreatment, while finer particulates are caught on cartridge filters before hitting high‑pressure skids.

Pressure exchanger periodic tasks

Monthly to semiannual tasks are geared to preserving the device’s tight clearances and measurement fidelity:

- Rotor cleaning: the rotor and end‑covers are flushed with fresh water or OEM‑recommended cleaner to remove salt crystals and biofouling; moderate scaling can impair clearances and rotation (www.tidjma.tn).

- Bearings and couplings: where present, external bearings or couplings are lubricated per OEM guidance (many PX devices have sealed, indefinite‑life bearings); coupling alignment is checked if a motor or geared drive is used because misalignment can preload the rotor.

- Instrumentation calibration: pressure and flow sensors around the ERD are verified so miscalibration does not mask issues.

- Performance trending: pressure drop and flow‑transfer efficiency are logged. A healthy PX shows only a few percent volumetric mixing (stream crossover) (energyrecovery.com). If effective transfer efficiency falls well below ~95% (www.frontiersin.org) or volumetric mixing rises toward ~5–10%, internal leakage or damage is suspected.

Spare sensor hardware and support equipment—flow meters, strainers, and housings—are often managed as water‑treatment ancillaries to keep these checks consistent.

Pressure exchanger annual shutdown

At scheduled outages (annual to multi‑year), units are disassembled for a detailed inspection. The ceramic rotor is checked for cracks or chips; housing seals are examined. If internal damage is present, the ceramic rotor cartridge is replaced. Field experience has shown decades‑old PX units often exhibit no life‑limiting wear (energyrecovery.com), but imperfections are removed regardless. Static seals, O‑rings, and bearings are inspected and replaced if needed. If a tower‑mounted PX uses oil, oil and filters are changed. Reassembly follows the OEM manual, with rotor orientation reconfirmed.

A predictive maintenance posture—monitoring parameters, setting alarms on deviations, and keeping operating logs—helps flag trends like increasing HPP power or rising pressure differentials before failures. Industry guidance also supports keeping spare rotors, seals, and bearings on hand and training ERD technicians (www.tidjma.tn). Availability figures around ~99.8% have been reported over many years (energyrecovery.com).

Pressure exchanger fault patterns

When performance drifts, the symptoms tend to cluster:

- Internal leakage (high volumetric mixing): performance monitoring may show elevated concentrate pressure relative to feed—pressure transfer is incomplete. Causes include microscopic rotor cracks/nicks, worn end‑cap seals, or foreign particles between rotor and housing. Diagnosis uses recovered flow vs. reject flow; a drop in flow yield signals inefficiency. Resolution involves shutdown inspection, rotor cartridge and seal replacement, thorough interior cleaning, and a post‑assembly pressure decay test.

- Incorrect installation or orientation: backward installation generates whoosh‑type noises and performance loss (www.manualslib.com). Abrupt humming or vibration prompts a check; re‑orientation with the “Concentrate” side to concentrate flow typically resolves it (www.manualslib.com).

- Air entrapment: air pockets cause noise and reduced pressure transfer; fluttering sounds and outlet‑pressure spikes are common on startup. Venting via bleed valves or purge flows is standard (www.manualslib.com).

- Membrane or system fouling: spikes in PX concentrate pressure can stem from severely fouled downstream membranes or from operating above design recovery. The remedy path is membrane inspection and cleaning or replacement, recovery adjustment, and flow re‑balancing to avoid starving or over‑feeding PX units; where applicable, adding parallel PX units is considered. Manufacturer guidance for excessive sound also cites over‑design flow, too‑low backpressure, air in system, or reversed installation—corrective actions include reducing flow, increasing feed pressure, bleeding air, and correcting orientation (www.manualslib.com, www.manualslib.com, www.manualslib.com). For unusually high concentrate pressure, causes include membrane scaling, excessive recovery, or pump over‑speed; solutions include membrane cleaning, lowering recovery, re‑balancing flows, and not exceeding PX flow rates (www.manualslib.com).

- Other faults: clogged screen filters upstream of the PX or malfunctioning feed pumps can disturb flow balance; if low‑pressure side flow drops below the high‑pressure side, mixing can occur (www.manualslib.com). Routine checks of upstream filters and pumps—often built around an automatic screen and a steel filter housing—support stable operation.

For severely damaged rotors or ceramic breakage, the manufacturer’s service department is contacted per the troubleshooting guide (www.manualslib.com).

On the membrane side, plants typically pair ERDs with robust RO stacks; membrane scaling control often relies on metered antiscalant programs delivered through a dosing pump and chemistry like membrane antiscalants to reduce downstream fouling risk during these troubleshooting cycles.

Turbine ERDs maintenance regime

Turbine‑type ERDs (Pelton wheels, Francis turbines, and turbochargers—sometimes driving pumps via VFDs, i.e., variable‑frequency electrical drives) typically operate at lower efficiencies than PX devices (~75–85%: www.frontiersin.org), yet remain widely used, often where upfront cost is pivotal (www.researchgate.net). Pelton ERDs can drive specific energy consumption (SEC, kWh per cubic meter of permeate) down to ~3.5–5.9 kWh/m³ on SWRO (www.frontiersin.org).

Routine inspection focuses on vibration, bearing noise, and leaks. Shaft seals are checked for brine leakage; Pelton nozzles are kept free of debris and correctly set. Output—electrical or torque—is tracked against expected values at given flow; declines point to wear or blockage. Bearing temperatures and shaft displacement readings are logged, alongside lubricant levels where oil is used.

Lubrication is foundational: bearings and gearboxes follow scheduled oil/grease changes—typical small hydro practice is 6–12 months or as specified by the manufacturer—with turbine‑grade lubricants selected for salt resistance. Water ingress or oil contamination triggers oil analysis. Proper lubrication is cited as critical to avoid cavitation damage and seizure.

Alignment between turbine and driven unit (pump or generator) is kept within tolerance; misalignment overloads bearings. Vibration analysis is used to verify alignment; excessive high‑frequency content leads to re‑alignment. Internals see periodic attention: every few years, Pelton buckets or Francis runners are inspected for pitting, erosion, and corrosion; worn blades are replaced. For Pelton units, nozzle condition and alignment are pivotal—worn/enlarged nozzles reduce efficiency. In integrated turbochargers, pump impellers and turbine stages are checked back‑to‑back.

Ancillary systems matter: control valves feeding the turbine must cycle smoothly; scaling can stick valves, provoking flow surges or cavitation at low flows. Electrical integrity is checked when a generator is present—connections, sensors, and safety interlocks are tested during shutdowns, with insulation resistance of generator windings verified annually. Torque‑limiting couplings or clutches are adjusted to absorb shock. Critical spares include bearings, seals, and wear rings, along with stocked greases, oils, and belts.

Maintenance intervals vary by size and duty, but the pattern is clear: monthly to quarterly checks on structure and lubrication, annual vibration and alignment checks, and multi‑year overhauls. In seawater service, a Pelton turbine typically receives a major overhaul every 3–5 years of continuous use (bearing/bucket renewal), whereas PX units can run for decades. Lock‑out/tag‑out is assumed for all interventions.

Turbine ERDs fault archetypes

Common failure modes are mechanical:

- Bearing wear and vibration: rising vibration spectra or bearing temperatures indicate wear or lubrication loss. Resolutions include adjusting preload (where applicable), repacking or replacing bearings, re‑aligning shafts, refilling lubricant, and replacing worn couplings.

- Cavitation or air fouling: changing inlet conditions (e.g., pump speed increases or outlet valve closure) can trigger cavitation, signaled by a gravelly flow sound and performance drop. Operation is kept away from the cavitation regime by maintaining rated flow; inlet strainers are checked for clogs.

- Obstructed nozzles (Pelton): biofouling or scale narrows jets, reducing impact force and efficiency; diagnosis includes lower generator output at fixed feed pressure or jet misdirection. Nozzles and orifice screens are removed and cleaned, worn needles are replaced, and jet alignment is set.

- Corrosion in piping: turbine skid piping can corrode or rust; leaks depress pressure and flow. Piping and welds are inspected, including for corrosion under insulation and at flanges, with immediate repair or replacement of affected sections.

- Electrical load drop: at fixed flow, lower generator output suggests mechanical loss. The sequence is coupling/belt inspection, then internal friction checks (potential rotor rubbing), then electrical diagnostics; turbine speed is confirmed against hydraulic input.

Severe damage is returned to the OEM. Unlike PX units, turbine ERDs have consumable parts (bearings, seals, nozzles), so replacement lives are tracked. Instrumentation supports a data‑driven approach: plotting turbine output (power or torque) versus brine flow over time surfaces downward drift early. Vibration analysis before and after bulb is strongly recommended, per standard rotating machinery practice.

Plants that also operate brackish lines or hybrid pretreatment trains coordinate these programs with their brackish‑water RO and wider membrane systems to keep upstream loads predictable for the ERDs. When membrane cleaning cycles are initiated, teams commonly lean on membrane cleaners to restore flux before retesting ERD balance.

Operational benchmarks and trends

Benchmarks anchor alarms. PX devices run at ≥95% transfer efficiency routinely (www.frontiersin.org), so dips below ~90% are red flags. Volumetric mixing is kept under 3% (energyrecovery.com); higher mixing points to internal leaks or misadjustment. Turbine ERDs sit nearer ~75–85% efficiency (www.frontiersin.org), so “normal” losses are larger.

Energy audits compare actual specific energy consumption to history; a shift from 2.5–3.0 kWh to 3.5+ kWh per m³ after maintenance indicates ERD performance loss or membrane fouling (www.frontiersin.org). Because SWRO energy is 40–45% of water cost (www.aesarabia.com), small ERD efficiency losses scale into large operating costs. Maintenance typically pays for itself quickly: restoring a PX to health recovers the ~15%+ energy advantage over turbines (www.frontiersin.org), while ignoring turbine wear erodes the expected ~25–30% energy saving.

Summary and maintenance economics

For Indonesian desalination plants (and elsewhere), rigorous ERD upkeep is essential. Pressure exchangers generally demand less maintenance than turbines, yet benefit from routine inspection, cleaning, and orientation checks (www.manualslib.com, www.tidjma.tn). Turbine ERDs require full rotating‑equipment discipline: lubrication, alignment, and blade checks. In both cases, instrumentation—pressures, flows, generator output, and vibration—enables early intervention, while spare‑part readiness (e.g., rotors, seals, bearings) and training keep availability high (energyrecovery.com). Done well, ERDs deliver near‑design efficiencies and long service life, maximizing energy recovery (e.g., 25–60% savings: www.slideshare.net, www.frontiersin.org) and minimizing downtime—the outcome that matters on the operating budget.

Membrane health is the final multiplier: when RO stacks are maintained with proven brands, whether Filmtec RO membranes or other lines, ERDs have consistent backpressure to work against. Replacement parts and consumables are typically organized through water‑treatment parts and consumables programs to keep interventions on schedule.