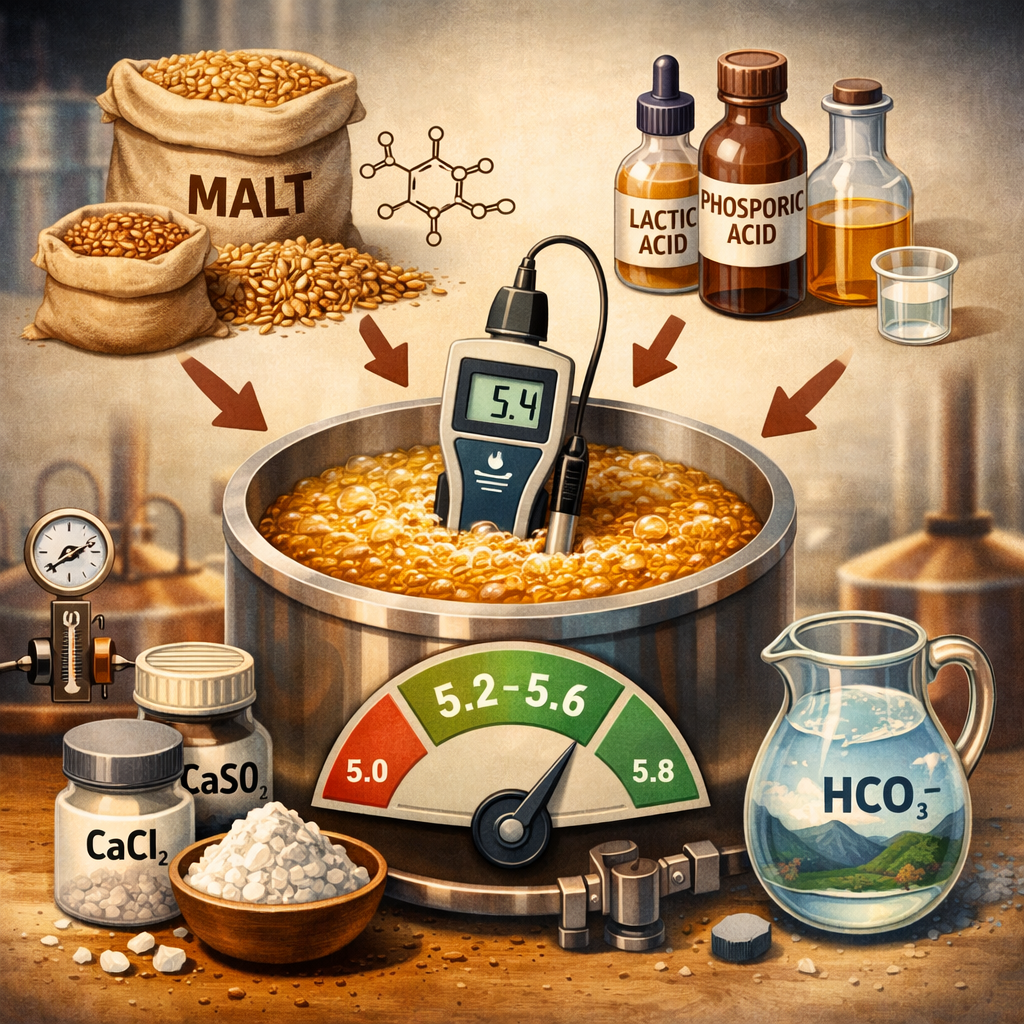

Mash pH sits in a tight sweet spot — roughly 5.2–5.6 — and getting there is a tug-of-war between acidic malt and alkaline water. Brewers win it with measured doses of lactic or phosphoric acid and carefully chosen calcium salts, all while outmuscling the mash’s strong buffer.

Industry: Brewery | Process: Mashing

Mash pH isn’t vibes. It’s chemistry with revenue consequences. Brewing scientists and industry sources agree the mash commonly lands near pH ~5.6 at room temperature, and the optimal range for enzyme work and flavor sits around 5.2–5.6 — a narrow window where α‑ and β‑amylases run hot and extraction is efficient (byo.com; byo.com). But the mash is a strong buffer, so moving the needle takes real acid/base, not hand‑waving (braukaiser.com; byo.com).

At stake is enzyme performance: β‑amylase activity peaks near pH ≈5.4–5.6 and α‑amylase around ≈5.6–5.8; drift much above ~5.6 and β suffers with a higher risk of tannin extraction, drop much below ~5.2 and α gets inhibited (byo.com). That’s why many brewers target ~5.2–5.4 at room temperature for best yield and consistency (byo.com; solenis.com).

Malt buffering and water alkalinity

Think of mash pH as a tug-of-war between malt acidity and water alkalinity (braukaiser.com; byo.com). Well‑modified malt brings organic acids (lactic, citric, succinic), phosphates from phytin breakdown, and soluble proteins/amino acids — a buffet of buffers centered around roughly pH 5–6 (onlinelibrary.wiley.com; braukaiser.com).

The buffer is strong. About 3–5 milliequivalents of acid per kilogram of grain — milliequivalents (mEq) are a measure of reactive acid/base amount — are needed to move mash pH by just 0.1 unit (braukaiser.com). In practice, that’s roughly 0.3–0.5 g of 88% lactic acid per kg of grain; in a 4 L/kg mash, about 0.08–0.15 g of 88% lactic per liter lowers pH by ~0.1 (braukaiser.com). Ditrych et al. (2024) found that even when wort was acidified at mash‑in to pH 5.0–6.0, the finished wort “gravitated toward the pH of the unadjusted wort,” underscoring the mash’s buffering power; only extreme acidification at mash‑in (pH 4.5) produced a substantially lower finished wort pH (tandfonline.com).

Grain bill and water chemistry tilt the balance. Roasted malts drive the mash more acidic — towards pH ~5.0 or lower — so dark beers often land near target without acid additions, while pale beers frequently need help to hit ~5.3 (byo.com). Water with high bicarbonate (alkaline) neutralizes malt acids and raises mash pH; residual alkalinity (carbonate/pH‑buffering capacity) can push pH above 5.6 unless countered — as seen in high‑bicarbonate profiles such as Burton or Munich waters (byo.com; braukaiser.com). In effect, the malt’s “acid side” must be balanced by the water’s “alkaline side” to finish in the 5.2–5.6 window (braukaiser.com; braukaiser.com).

Acid dosing: lactic vs phosphoric

Direct acid additions are the cleanest lever for lowering mash pH. Lactic acid (typically 80–88% solution) is the workhorse; as a weak organic acid, it yields lactate and, used judiciously, is not flavor‑active. Ehling reports up to 0.25 g/L of 88% lactic — approximately equal to 4% of the grist as acidulated malt — with no perceptible sourness (braukaiser.com). In practice, only small volumes are needed: ~0.3–0.5 g per kg of grain typically lowers mash pH by ~0.1, so a 20 kg grist on 80 L water (~0.25 kg/L) might require about 6–10 g lactic acid — roughly 7–12 mL of an 88% solution — to trim pH ~0.1. Ahye and Kirsop (1968) showed that small additions of H⁺ from lactic neutralize wort bicarbonate (CO₂) and lower pH.

Given lactic’s recent tight supply, many breweries reach for 75% food‑grade phosphoric acid (solenis.com). It’s stronger, so dosed in much smaller amounts: by Ehling’s table, 1 mEq corresponds to ~0.198 g of 75% phosphoric, meaning the same 3–5 mEq per kg of grist equates to only ~0.6–1.0 g of acid — less than lactic. Phosphoric also replaces bicarbonate with phosphate in the water; that extra phosphate load is minor relative to malt phosphate and doesn’t appreciably precipitate calcium (braukaiser.com). It’s effectively flavor‑neutral and “takes much less to drop the pH” than lactic, which is why it’s often used in modern Pale Ales or IPAs (solenis.com).

Other food acids show up less often. Acetic acid (vinegar) can acidify the mash but brings vinegar flavor and is mainly used in sour styles. Citric acts similarly to lactic but can add slight citrus notes. In Germany, only lactic (or lactic from acidulated malt) is officially permitted as a mash acidifier (braukaiser.com). Brewers generally avoid strong inorganic acids (HCl, H₂SO₄) in the mash for safety and flavor reasons, though they can be applied in water treatment; HCl would replace bicarbonate with chloride (risking a saline taste) and H₂SO₄ would replace it with sulfate (which can accentuate hop bitterness) (braukaiser.com).

For granular control during small correction steps, accurate chemical dosing equipment is relevant; brewhouses may specify a dosing pump for milliliter‑scale acid additions.

Acidulated malt and sour mash options

Acidified malt — “sauer malt” or “phosphatase malt” — is pale malt sprayed with lactobacillus or lactic and dried to ~2–3% lactic. Swapping 1–3% of the grist to acidulated malt typically lowers mash pH by roughly 0.1–0.3 units; for example, ~2% acid malt can drop pH ~0.2 in a soft‑water mash (braukaiser.com; braukaiser.com). Sour mashes (steeping part of the grist with lactobacilli) achieve the same effect. These organic routes are gentler, introducing lactic naturally, but they’re slower than direct dosing.

Mineral additions and pH

Calcium salts nudge mash pH down by reacting with malt phosphates to release H⁺ in the mash. Calcium chloride (CaCl₂) and gypsum (CaSO₄) supply Ca²⁺ without adding bicarbonate, with flavor differences: gypsum favors a crisper, bitter profile; CaCl₂ enhances maltiness and fullness. For pH, it’s the calcium that matters (byo.com; braukaiser.com). Raising mash Ca²⁺ to ~150 ppm (with negligible alkalinity) can drop mash pH by ~0.1–0.2 units depending on mash thickness; in practice, brewers might add ~1–3 g/L of gypsum or CaCl₂ to lift water calcium by 50–100 ppm and get about that much pH reduction (braukaiser.com). Magnesium salts (MgSO₄, MgCl₂) behave similarly but are costlier and less impactful on pH; they’re seldom used for pH control (braukaiser.com).

Salts that add alkalinity (bicarbonate) drive pH up and are reserved for over‑acidic mashes: chalk (CaCO₃), sodium carbonate, or sodium bicarbonate. A stout mash below pH 5.0, for example, might get a small addition of CaCO₃ or pickling lime (Ca(OH)₂). CaCO₃ neutralizes two H⁺ per mole — about half the acid of one mole of lactic — and roughly 1 g/L can raise pH by a few tenths, though overuse risks haze or scale; sodium bicarbonate is more soluble but can taste salty if overdone (braukaiser.com). The focus here is lowering pH; these are safety valves for overshoot.

High mash pH (>5.6) causes and fixes

High readings usually trace to high‑carbonate water or very light grists. Hard, alkaline water — e.g., Dublin or some Asian waters — tends to push mash above 5.8. An all‑pilsner mash with too little calcium will also sit high; in fact, a distilled‑water mash of Pilsner malt alone falls only to ~5.5–5.6 (braukaiser.com). Fixes include removing alkalinity or adding acid: dilute with softer water, boil/“decant” high‑bicarbonate water to precipitate temporary hardness, or add food‑grade acid to the mash. For minor corrections, a few mL/L of 88% lactic or 75% phosphoric, applied per the 3–5 mEq guideline, typically does the job (braukaiser.com).

One example in the numbers: at pH 5.8 on a 20 kg grist, ~6–10 g of 88% lactic (3–5 mEq/kg) might land ~5.5. Always re‑check pH after additions; the mash’s buffering can hold pH steady until enough acid is present. Also verify that the meter is calibrated and that measurements are taken on cooled samples (RT, room temperature): measurements in uncooled mash without ATC (automatic temperature compensation) can appear higher than the true conversion pH (byo.com). In short: if starch conversion or efficiency seems low and mash pH is high, add acid/lautenzulsatz (acid malt) or switch to lower‑alkalinity water — some brewhouses secure low‑alkalinity dilution via dedicated membrane systems.

Low mash pH (<5.2) remedies

Low mash pH is uncommon in pale ales; it shows up in very dark beers with heavy roast percentages. First, check for over‑applied acids. To raise pH, add a small sprinkle of food‑grade chalk or baking soda with steady stirring. High calcium without alkalinity can produce a modest rise by neutralizing parts of the malt buffer, but bicarbonate additions are more effective for raising pH. If lactic overshot the target, consider diluting the mash or adding CaCO₃. Ehling’s caveat applies: CaCO₃ only neutralizes about 50% as much acid per weight as lactic, and excessive base can strip too much calcium (braukaiser.com). In practice, careful blending or dilution tends to be safer than large chemical doses.

Measurement practice and pH drift

“Unexpected” pH drift often isn’t the mash — it’s the measurement. Common culprits include poor meter calibration, hot break particles interfering with the probe, or reading hot samples. Calibrate immediately before use, let samples settle or filter briefly, and measure at ~20–25 °C with ATC on. Wort pH rises as it cools: a mash that looks 5.3 at ~65 °C may read ~5.5 when cooled; if the chilled sample reads high, it truly is high and needs acid (byo.com).

Efficiency and flavor impacts

Above ~5.6, α‑ and β‑amylases underperform; extract yield can drop by a few percent — a line‑item problem at scale. Practical experience suggests even a 0.1–0.2 unit correction toward the ideal range improves attenuation and consistency. Below ~5.2, expect risks of astringency from excessive tannin extraction and incomplete starch breakdown since α‑amylase is suboptimal at low pH (byo.com). The playbook is systematic water adjustment (salts and acids) and consistent pH measurement, with prediction models (e.g., Bru’n Water, mash chemistry models) helping with first‑pass estimates — always verified by the meter.

Quantitative rules of thumb

Two practical anchors recur in the literature. First, plan on ~0.1 pH drop per 3–5 mEq of acid added per kilogram of grist (braukaiser.com). Second, a ~150 ppm boost in Ca²⁺ (with low alkalinity) typically yields ~0.1–0.2 pH reduction, with ~1–3 g/L of calcium salts often used to raise water calcium by 50–100 ppm (braukaiser.com). Combine these with diligent pH monitoring and brewhouses can minimize mash inefficiency and off‑flavors.

Sources and enzyme targets

Core science and guidelines are detailed across brewing literature and industry sources cited above: comprehensive primers and Q&A from byo.com, modeling and dosage data from braukaiser.com, peer‑reviewed perspectives such as Li et al. 2016 (onlinelibrary.wiley.com) and Ditrych et al. 2024 (tandfonline.com), and acid selection notes from solenis.com. The upshot is consistent: aim for 5.2–5.6 (room‑temperature measurement of cooled wort) for enzyme activity and flavor (byo.com; solenis.com).

Troubleshooting tips (summary)

- High mash pH: Use calculated acid/salt additions (lactic, phosphoric, gypsum) or reduce water alkalinity. Measure pH after cooling; target ~5.3.

- Low mash pH: Add small amounts of CaCO₃ or bicarbonate; decrease acidulated malt. Check that no overshoot of acid.

- Meter error: Calibrate carefully; account for ~+0.2–0.4 pH shift from 65 °C to 20 °C (byo.com). Ensuring correct equipment and procedure often resolves “mystery” pH issues.

- Extraction problems: If conversion is poor, verify mash pH is in range. Correcting pH by even 0.2–0.3 units (using the buffer estimates above) can measurably improve efficiency and reduce mash time.