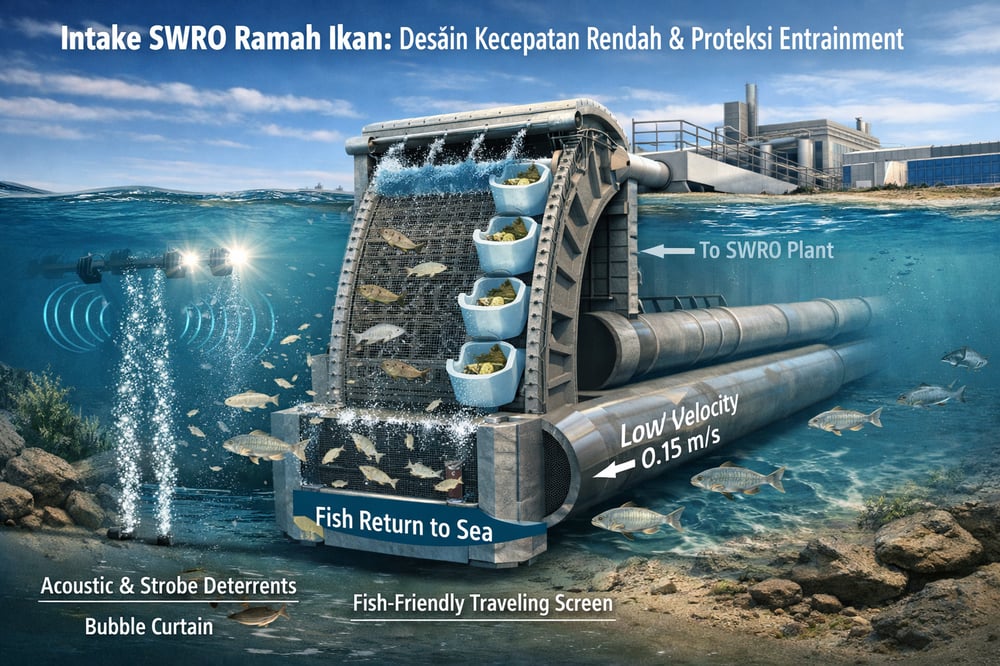

Modern seawater intakes are engineered to let water in and keep fish out. The winning playbook: ultra‑low approach velocities, fish‑friendly traveling screens with gentle buckets, and acoustic or light deterrents that deflect entire schools before they reach the grate.

Industry: Desalination | Process: Seawater_Intake_&_Screening

Keep the water; spare the fish. Best‑practice seawater intake screens now use very low approach velocities (water speed at the screen face) and non‑abrasive meshes so fish can swim away rather than be pinned — a phenomenon known as impingement (organisms held against a screen). Keeping approach velocity at or below about 0.15 m/s (0.5 ft/s) allows most fish to avoid being held against the screen (scribd.com).

Where fish do contact the screen, traveling screens modified for fish protection — notably Ristroph‑style band screens with low through‑screen velocities and fish‑lifting buckets — move them gently out of the flow (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

Approach velocity and open area

Velocity matters. Designs targeting ≤0.15 m/s are consistent with a “no‑entrainment” criterion (entrainment: organisms drawn through an intake) used in California, and studies show fish freely escape intakes when water velocity is <0.15 m/s (scribd.com). Hydraulic modeling of passive wedge‑wire screens (wedge‑wire: smooth V‑shaped wire forming narrow slots) demonstrates how added baffles equalize flow and can cut peak inlet velocity from >2 m/s to ~0.05–0.08 m/s (mdpi.com).

High open‑area passive screens help. Commercial wedge‑wire units commonly deliver ~90% open area with <3 mm slot openings, specified to hold intake velocities under 0.15 m/s so flow remains low across the entire surface (herofilters.com).

Traveling screens with fish‑lifting buckets

The signature of “fish‑friendly” traveling screens is gentle handling. Smooth, non‑abrasive meshes and leading‑edge buckets with curved lips reduce turbulence (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com). Envirex polymer baskets — 6.4×12.7 mm rectangular smooth mesh — were adopted at the Salem power station to increase open area and reduce pressure on impinged fish (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com); similar screens achieved nearly zero fish mortality in subsequent tests (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

Modern systems operate continuously rather than batch‑clean, so fish are quickly rinsed off by low‑pressure sprays into a collection trough (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com). Each ascending bucket holds fish in a small water‑filled chamber over the top of the screen; a continuous spray then washes them into a gravity sluice or pump that returns them to source waters, minimizing out‑of‑water time (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (nepis.epa.gov). The same continuous‑removal principle underpins intake headworks that use automatic screen equipment; in desalination service, that mode aligns with automatic screens designed for continuous debris removal.

The survival data are striking. Laboratory trials of modified traveling screens reported over 13,000 fish (10 species) surviving impingement at approach speeds up to 0.9 m/s with ≤5% mortality in all cases — “mortality rates did not exceed 5% for any species and velocity tested,” with larger fish generally faring better than small juveniles (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com). Regulators echo the potential: traveling screens modified for fish protection can prevent impingement losses when operated as described (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

Passive wedge‑wire intake screens

Passive screens can deliver similarly low velocities with minimal head loss. Wedge‑wire units advertised with <3 mm slots emphasize smooth slots and low velocity through the entire screen surface, with high open area (~90% or more) to protect aquatic life (herofilters.com). Modeling confirms that flow‑deflecting baffles on such screens can drive peak inlet velocities down to ~0.05–0.08 m/s (mdpi.com).

Design guidelines in practice

Approach velocity: target ≤0.15 m/s (0.5 ft/s) through the screen — a level that allows most fish to swim away; fish escaped an open offshore intake when velocity was <0.15 m/s (scribd.com) and modeling shows optimal ranges around ~0.05–0.08 m/s (mdpi.com).

Mesh/opening size: use fine, smooth mesh (plastic‑coated or woven) with openings sized to protect the smallest life stage of concern; many designs go to 0.5–1.0 mm to block eggs/larvae, while fish buckets handle larger fish (scribd.com) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

Fish buckets and returns: incorporate rising buckets or a “fish elevator” so impinged fish are never crushed; buckets should have curved/flared leading edges and be filled with water to suspend fish, as pioneered by Ristroph (1976) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com). Continuous screen rotation plus low‑pressure spray moves fish into a collection trough each cycle, then a gravity flume or pump returns them at a safe location (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (nepis.epa.gov).

Materials and durability: corrosion‑resistant alloys (e.g., duplex stainless) or composites allow thinner wires and larger open area; Envirex composite baskets increased open area and reduced water force on fish (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (see wedge‑wire dimensional options here: herofilters.com).

Location and redundancy: site intakes away from sensitive habitat; run multiple screens in parallel to lower velocity per screen; maintain automated cleaning to prevent clogging spikes that would raise velocity — a continuous‑removal mode typical of automatic screens.

Acoustic deterrent arrays

Non‑physical deterrents push fish away before they reach the screen. Acoustic systems use underwater projectors to emit low‑frequency sound fields matched to fish hearing. In the field, a 20–600 Hz system at an estuarine power intake cut total impingement by about 60% (species‑dependent), with schooling clupeids deflected by 94.7% (herring) and 87.9% (sprat), while bottom‑dwellers such as lamprey and flatfish were largely unaffected (researchgate.net).

Scale that up and results can be dramatic. At Belgium’s Doel nuclear plant, a 20‑projector array running 30–600 Hz signals tailored for herring/sprat achieved a 98% reduction in target species and an 81% overall reduction in intake catch (neimagazine.com). The best performance depends on modeling the sound field to avoid “nulls” and properly cover the intake zone (neimagazine.com) (neimagazine.com).

Effectiveness varies by species and context; one review notes 3–40% of a population penetrated deterrents in some trials, and fish may habituate if signals aren’t varied (researchgate.net) (neimagazine.com).

Light and bubble visual barriers

Strobe (stroboscopic) lighting offers a visual barrier. Controlled trials reported 8–100% avoidance depending on species and conditions; white perch, spot, and Atlantic menhaden showed strong aversion at ~300 flashes/min, especially in turbid water (avoidance up to 81%), but little effect in clear conditions (nepis.epa.gov). As EPRI noted, strobes tend to outperform constant mercury‑vapor lamps as barriers (nepis.epa.gov).

Bubble curtains and mixed systems combine modalities. In a Bio‑Acoustic Fish Fence (BAFF), dense rising bubbles carry sound and create a visible “fence” that schooling fish avoid; such barriers used at hydropower intakes have potential for desalination intake perimeters (neimagazine.com). Effectiveness varies — some species cross, others avoid — but bubbles can enhance acoustic reach and form a 3D barrier. A synthesis concludes that combined systems (sound + light + bubbles) may yield moderate effectiveness with high variability by species (mdpi.com) (neimagazine.com).

Costs, power draw, and maintenance

Behavioral systems are relatively modest line items compared to compliance risk. Acoustic systems and BAFFs typically cost on the order of 10^4–10^5 USD and draw modest power — around 1 kVA per projector (neimagazine.com). Strobe lights cost less (a few thousand dollars for multiple fixtures). All require power, controls, and periodic maintenance (e.g., speakers and moving parts). Some retrofit acoustic arrays have been installed for ~£50k–200k (neimagazine.com).

Regulatory context and best technology

Under the U.S. Clean Water Act, Section 316(b) requires that cooling and process water intakes minimize adverse impacts on fish and other aquatic life (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com). This has driven adoption of fish‑friendly screens and deterrents at power stations and desalination plants. A California task force similarly recommends zero‑impingement intake flows. While Indonesia’s regulations currently do not detail intake fish screens, any coastal intake would be expected to follow international best practices (as embodied in EPA/EPRI guidelines) to avoid harming local fisheries.

In practice, regulators and operators treat deterrents as supplementary — to complement, not replace, physical screens. Even the Doel array saw a residual catch of ~19% (100%–81%) (neimagazine.com).

Measured outcomes at intakes

Analyses of large desalination projects note that “the daily intake impingement impact is less than the daily fish intake of one pelican” (researchgate.net) (Voutchkov 2011). The U.S. EPA’s 316(b) review emphasizes that traveling screens modified for fish protection and operated continuously “have the potential to prevent impingement losses” (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com). Moving to the best technology available — fine‑mesh modified screens with fish returns — can make impingement mortality almost zero (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com).

The trend is clear in modern desalination and cooling‑water intakes: use the lowest practical approach velocity with advanced screens, add fish‑return systems so impinged organisms are immediately released, and supplement with acoustic and light deterrents. Case studies report target‑species reductions of 60–98% when acoustic arrays are well designed (researchgate.net) (neimagazine.com), and operators routinely see fish catch at intakes drop by an order of magnitude — a change that typically justifies the modest incremental cost of these technologies.

Sources and technical references

Peer‑reviewed studies and technical reports (EPA 1973/1994, Water Research Foundation 2011) provide design guidance and empirical results. Key references include Black & Perry (2014) on screen survival (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com) (afspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com); Maes et al. (2004) on acoustic deterrents (researchgate.net); Turnpenny et al. (1993, summarized in NEI 2012) on barrier systems (neimagazine.com); and hydraulic analyses of intake screens (scribd.com) (mdpi.com). All data cited above come from these sources.