Seawater RO produces about 60% of the world’s desalinated water, yet biofouling is the single biggest technical challenge operators face. The new playbook: smarter diagnosis, targeted cleaning chemistries, and pretreatment biocide programs backed by real‑time monitoring.

Industry: Desalination | Process: Reverse_Osmosis_(RO)

Seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) — the workhorse pressure‑driven membrane process for turning seawater into fresh water — now accounts for roughly 60% of global desalination output (www.intechopen.com). But as operators of SWRO systems know, biofouling sticks to the top of the risk register: it is cited as the single biggest technical challenge in the field (kremesti.com).

Once microorganisms colonize membrane active layers, plants see feed‑channel pressure (FCP, the pressure drop along the spiral‑wound feed spacer) spike, permeate flux slide, and salt breakthrough emerge — the trifecta that forces frequent clean‑in‑place (CIP) and burns through membranes (www.intechopen.com). As the desal market expands at ~10–15% annually (kremesti.com), and with biofouling already making up ~30% of the RO chemical market (projected to rise) (kremesti.com), the economics of getting ahead of slime are obvious.

Two industry shifts underscore the response: a move away from blanket continuous chlorination toward hybrid or intermittent strategies, and a surge in ultrafiltration (UF) pretreatment — from under 200,000 m³/d in 2004 to over 1,000,000 m³/d by 2008 (kremesti.com).

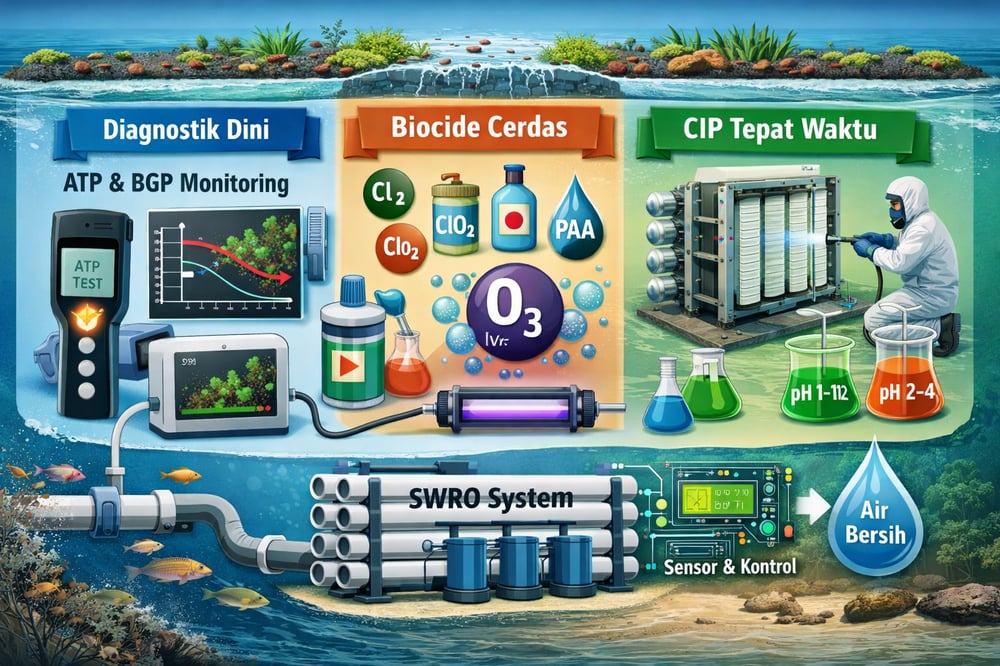

Diagnosis: performance signals and growth‑potential metrics

Biofouling usually hints its arrival via plant KPIs: a rising normalized feed‑to‑brine pressure drop or declining permeate flux at constant recovery (www.intechopen.com). A ~15% increase in FCP typically triggers CIP (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Element autopsies (SEM/FTIR/biomass assays) can confirm biofilm and speciate it, but they come after performance loss.

Operators now layer in biofouling‑potential tests. ATP‑based or flow‑cytometry Bacterial Growth Potential (BGP) assays quantify nurturable biomass in feedwater. In one SWRO plant, flow‑cytometry BGP after DAF–UF pretreatment at ~0.5 mg Fe³⁺/L reached ~1.5×106 cells/mL — 25% higher than after DMF–CF pretreatment — and the higher‑BGP line needed more frequent CIP (www.mdpi.com). An ATP BGP range of 100–950 µg‑C/L (as glucose) in SWRO feed tracked directly with increased membrane ΔP, while standard SDI (silt density index) or MFI (modified fouling index) often stayed low and missed onset (www.mdpi.com).

For context, a classic freshwater biofouling threshold is ~10 µg‑C/L of AOC (assimilable organic carbon) (www.mdpi.com). In seawater, baselines are much higher — ~817 µg/L in one study (www.mdpi.com) — but relative changes still guide action.

Online simulators are emerging to catch early signals. Toray’s mBFR column flows SWRO feed through a small RO membrane and reads pressure rise as biomass accumulation in real time (www.water.toray). Studies suggest keeping mBFR below ~10 pg‑ATP/cm²·day avoids rapid fouling (www.researchgate.net) (www.researchgate.net). Membrane fouling simulators (MFS) and “biofilm formation rate” probes mimic module behavior; they mirror what’s already occurring, so consensus is to combine them with growth‑potential assays. For Indonesian operations, any monitoring data tied to treatment changes must still meet permitting: brine discharge to sea requires a permit and quarterly effluent reporting under Permen LH 12/2006 (www.nawasis.org).

Pretreatment trains and biocide selection

Prevention starts upstream. Conventional trains — screening, coagulation/flocculation, dual‑media filters, then cartridge filters — remain widely used for cost reasons (kremesti.com). Upgrading to dissolved‑air flotation (DAF) or to ultrafiltration (UF) markedly improves biological stability. In pilot work, DAF–UF pretreatment with ~0.5 mg/L Fe³⁺ cut BGP by 54%, while weaker flocculation achieved 40%; these gains doubled or tripled CIP intervals versus weaker pretreatment (www.mdpi.com). At full scale, DAF plus coagulation (1–5 mg/L Fe³⁺) removed ~70% of orthophosphate and ~50% of BGP, versus ~10% removal of high‑molecular‑weight humics (www.mdpi.com). UF/MF pretreatment — now ~10–20% of installed capacity (kremesti.com) — stabilizes feed by reducing ultrafine particulates, viruses, and ~30–60% of organic colloids (kremesti.com), though it cannot fully strip nutrients or dissolved organics.

Biocide strategy is central. Most plants dose onsite‑generated chlorine at 0.5–2 mg/L as free Cl₂ because it is effective and inexpensive (kremesti.com), often via electrochlorination units, with all residual quenched (e.g., sodium metabisulfite) before RO because polyamide membranes are chlorine‑sensitive (kremesti.com). Over‑chlorination has drawbacks: it can fragment natural organic matter into smaller AOC that fuels survivors (www.intechopen.com) and generates disinfection byproducts (THMs, HAAs) that must be monitored. To mitigate, plants adopt low‑dose chloramination (monochloramine) or on‑demand chlorine dioxide — deeper penetration and fewer volatile byproducts, though weaker killers (kremesti.com).

Ozone is another oxidant where contact tanks exist, albeit with a bromate‑formation risk in seawater. Peracetic acid (PAA) pulses appear in some open‑intake systems; PAA is a strong oxidizer that degrades to acetic acid and water with no chlorinated byproducts. UV disinfection, deployed mainly after sand and activated‑carbon filters, inactivates microbes without chemical residual (kremesti.com). Whatever the approach, biocide dosing must respect Indonesian limits on residuals and discharge permitting (Permen LH 12/2006) (www.nawasis.org), with tight control over setpoints (0.5–2 mg/L) enabled by modern dosing pumps. Notably, industry is trending toward intermittent or no continuous pretreatment disinfection when upstream nutrient removal is very effective (kremesti.com).

CIP chemistries and stepwise sequences

Even with robust pretreatment, biofilms accrue, and periodic CIP is unavoidable. Manufacturers prescribe alternating high‑pH and low‑pH sequences with specialized membrane cleaning formulations. A typical regimen: circulate 0.5–2% sodium hydroxide (often with surfactants, enzymes, or a mild oxidant) at pH ~11–12 for 30–60 minutes, then 0.5–2% citric or hydrochloric acid at pH ~2–4 for ~30 minutes, both at ~30–40 °C if permitted. The alkaline step saponifies fats and hydrolyzes proteins, lyses cells, and loosens extracellular polymeric substances (EPS); many cleaners add oxidizers such as hydrogen peroxide, percarbonate, or persulfate — hydrogen peroxide at ~0.1–0.5% is common in the NaOH stage. The acid step dissolves inorganics (carbonates, iron oxides) and chelates; citric acid is favored for safety and chelation, while stronger formulations (e.g., phosphoric acids with inhibitors) target refractory iron. Surfactants and chelators (e.g., EDTA) aid detachment, and some trains add a neutral rinse.

Choice matters. In an autopsy study, a two‑step clean using only 6% NaOH + 6% citric acid (manufacturer recommendation) underperformed a multi‑step protocol that added oxidants. Two lab protocols (“Cleaning A/B”) used just 3% NaOH but included sodium hypochlorite, hydrogen peroxide, and HCl in sequence; they left much lower residual microbial counts than the simple base/acid clean (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). This confirms oxidizers significantly improve biofilm kill beyond alkalinity alone (in practice, avoid free chlorine on polyamide active layers; hydrogen peroxide is safer at moderate dose). Enzymatic cleaning — adding protease and glycosidase to a mild pH (8–9) detergent — has broken down EPS in lab tests and reduced polysaccharide‑induced refouling; it is “promising,” though field use is limited by cost and biofilm complexity (pubs.acs.org).

Effectiveness wise, proper CIP typically restores ~80–90% of original flux. No sequence fully eradicates mature biofilms — top layers are removed, deeper cells persist — and repeated CIPs can select hardy species and shorten membrane life via chemical and thermal stress (www.intechopen.com) (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). That reality pushes plants to optimize CIP frequency with better early‑warning tools.

Online sensors, simulators, and composite indices

New optical probes blend UV/visible absorption and fluorescence to track organics and algal pigments in real time. One example, the SpectroMarine sensor, quantifies dissolved organic carbon and chlorophyll with fluorescence‑aided spectroscopy and streams data via IoT; field trials showed real‑time organic alerts let operators cut backwashing, save energy, and reduce chemicals (e.g., lower coagulant/chlorine doses when feed quality improved) (www.frontiersin.org) (www.frontiersin.org). Notably, SpectroMarine operated 5+ months without maintenance (www.frontiersin.org).

Inline biological indicators (e.g., portable ATP luminometers) can approximate BGP/EPS in minutes, and rapid AOC bioassays flag nutrient pulses. Simulators such as MFS or Toray’s mBFR quantify biofilm accumulation dynamically; keeping mBFR under ~10 pg‑ATP/cm² per day has been associated with 4–7+ months between CIPs (www.water.toray) (www.researchgate.net) (www.researchgate.net). Upward trends in these devices typically trigger raw‑water checks or pretreatment adjustments.

Many operators now compile composite biofouling indices — SDI, turbidity, orthophosphate, BGP — because at full‑scale one audit found SDI/MFI were always compliant (<3) while BGP better explained actual pressure behavior (www.mdpi.com). In short, pairing conventional fouling indices with BGP or AOC gives a more reliable risk readout.

Compliance requirements and OPEX outcomes

Indonesia‑specific obligations apply even as technology evolves. Plants must hold marine discharge permits and file quarterly effluent reports under Permen LH 12/2006, with spent cleaning liquids neutralized to meet marine discharge quality (www.nawasis.org). If product water enters a potable network, it must meet national drinking standards, including limits on disinfectant byproducts (e.g., PERMENKES 119/2014, for example). Indonesian law does not yet mandate specific RO biofouling monitors, but stable operation avoids unplanned CIP and effluent swings — indirectly supporting compliance (www.nawasis.org).

The business case is quantifiable. One review notes that reliable biofouling monitoring improved plant reliability, cut chemical use, and lowered production costs (www.intechopen.com). Another argues a pivot from total disinfection to “fuel‑for‑bacteria” control can trim pretreatment chemical bills by ~40% (kremesti.com). This underpins a shift from calendar‑based to condition‑based cleaning: delay CIP until sensors flag suboptimal feed, protecting membrane life and uptime.

Summary metrics and practical outcomes

Integrated fouling management — from intake through final RO — now blends nutrient‑focused pretreatment, tuned biocide programs, targeted CIP chemistry, and monitoring. Effective pretreatment alone can remove >50% of biofouling potential (www.mdpi.com) (www.mdpi.com). When fouling occurs, sequential high‑pH and low‑pH cleaning — with oxidizers or enzymes — strips biofilms more effectively than base/acid alone (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) (pubs.acs.org). Ongoing monitoring — BGP/ATP assays, optical sensors, and fouling simulators — enables just‑in‑time cleaning, often stretching CIP intervals from monthly to quarterly (or longer). One measured example: pretreatment that cut feed phosphate by ~70% and BGP by ~50% halved the normalized pressure drop rate (www.mdpi.com).

Ultimately, data‑driven biofouling control — aligned with regulation (e.g., Permen LH 12/2006) (www.nawasis.org) — offers the best assurance of reliable, cost‑effective desalination on modern SWRO trains and complements UV polishing where appropriate via UV systems.