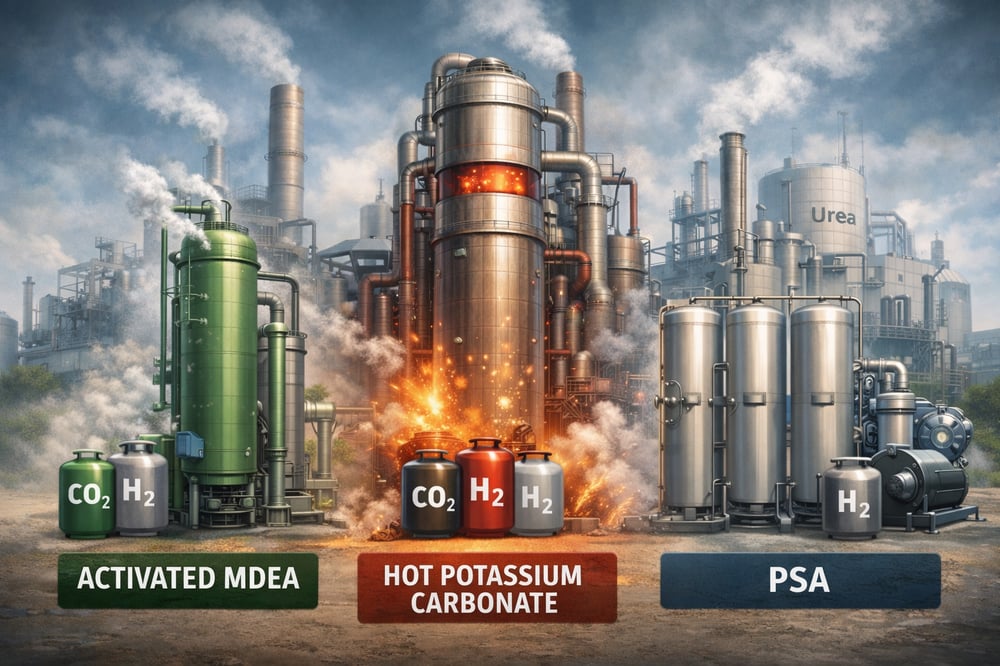

Ammonia makers have three main ways to strip CO₂ from syngas: activated amine solvents, hot potassium carbonate, or pressure swing adsorption. Each route trades steam for electrons, capex for operating complexity, and purity for capture rate.

Industry: Fertilizer_(Ammonia_&_Urea) | Process: CO2_Removal

Ammonia plants built around steam reformers or gasifiers churn out a syngas cocktail of H₂, N₂, CO₂ and CO. To feed the Haber–Bosch synthesis loop and integrate with urea units, the CO₂ (“acid gas”) has to go — typically at ≥90% removal. Globally, with ~140 Mt NH₃ produced in 2018 (www.sciencedirect.com), chemical absorption dominates. The workhorses are activated amines such as MDEA (methyldiethanolamine) blends and hot potassium carbonate; a third path uses PSA (pressure swing adsorption) hardware to purify hydrogen and deliver a CO₂‑rich tail.

Below is a comparative look at how these technologies perform, their energy bill, and where each fits — with selection guidance for process engineers whose economics hinge on steam and electrons.

Activated amines (MDEA + promoter)

MDEA blended with an activator (often piperazine or a glycolamine) is widely applied for bulk CO₂ removal in ammonia syngas (www.mdpi.com) (www.mdpi.com). In the classic absorber–stripper loop, the regeneration step (lean–rich amine “stripper”) is steam‑hungry: base cases run at about 3.2–3.6 GJ per tonne CO₂ (3.2–3.6 MJ/kg) (www.researchgate.net) (www.mdpi.com). One simulation of a 35% MDEA/15% piperazine blend capturing 90% CO₂ reported a 3.235 MJ/kg CO₂ reboiler duty; advanced splits/compression can trim this toward ~2.78 MJ/kg (www.researchgate.net).

Capture efficiency typically lands around 90–99%, with the CO₂ product essentially pure after water condensation (www.mdpi.com). Advantages: a mature base of references, high CO₂ loading, and low vapor losses. Drawbacks: high thermal duty (steam), large columns, amine corrosion/degradation concerns, and moderate solvent OPEX; capital cost is moderate, and advanced amines are often in the ~50–100 €/tCO₂ total capture cost range (depending on steam price and scale). For context, pure MEA systems are often 3.5–4 GJ/tCO₂ (www.mdpi.com), so MDEA/Pz performs somewhat better.

Commercial amine packages in this class include formulated options for CO₂/H₂S service, such as CO₂/H₂S removal amine solvents.

Hot potassium carbonate (Benfield/Catacarb)

Potassium carbonate (K₂CO₃) solutions — often promoted with glycine or borate — absorb CO₂ at elevated temperature (about 90–130 °C) and pressure. Energy duty is lower than amines: roughly 2.2–2.5 GJ/tCO₂, plus about 770 kWh/tCO₂ of electricity for circulation and pumps (emis.vito.be) (emis.vito.be). Typical capture ranges 80–95% at high feed pressure (≥20 bar), yielding ~99% pure CO₂ product (emis.vito.be) (emis.vito.be).

The inorganic solvent’s low volatility underpins its cost profile: EMIS cites CAPEX ~24 €/tCO₂ and OPEX ~60 €/tCO₂ for an 85% capture case (≈84 €/t total with 95% capture) (emis.vito.be). Hot‑carbonate favors large, high‑pressure syngas flows common in gas‑based ammonia and has solid corrosion behavior, but slower kinetics mean large columns; designs often use enriched packing and operate at ≳25 bar to boost absorption. Example: Andritz Catacarb® “hot potash” units are used industrially, with reported ~2.3 GJ/t duties (emis.vito.be).

PSA systems for hydrogen and CO₂

PSA (pressure swing adsorption) cycles remove impurities on adsorbents (zeolites/silica gel) at high pressure, then desorb at low pressure. In ammonia service, PSA is typically placed after shift to deliver ultra‑high‑purity hydrogen — 99.9–99.999% H₂ — at ~80–90% recovery, while the “tail gas” concentrates CO₂ and inerts (www.airproducts.ie). Configured correctly, PSA can co‑produce a CO₂‑rich stream: a multi‑stage PSA on steelworks off‑gas delivered ~96.9% CO₂ (75% recovery) and 99.3% H₂ (80% recovery) (www.mdpi.com).

Thermal energy use is minimal, but compressors/vacuum mean significant electrical power. The cost structure shifts accordingly: capital‑intensive columns, no big reboilers or solvent circulation. Reported PSA capture costs can be as low as £17/tCO₂ (~20 €/t) in a steel gas case (www.mdpi.com). PSA also avoids solvent handling, and its CO₂ product exits at moderately high pressure — an advantage if compressing for storage. A typical limitation: PSA is tuned for hydrogen‑rich feeds. If N₂ is present upstream (as in syngas straight from SMR/shift), an initial separation or specific co‑adsorption strategy is needed; in practice, many ammonia plants deploy PSA to isolate hydrogen after shift, then recombine with N₂ from an ASU (air separation unit) for Haber synthesis.

Performance and cost snapshots

CO₂ capture efficiency: solvent systems routinely reach 80–99% (e.g., 90% for the MDEA/Pz case, www.mdpi.com; up to 95+% for hot K₂CO₃ at pressure, emis.vito.be). PSA can leave a CO₂‑rich tail and, in practice, has trapped about 75% of CO₂ into a ~97% pure product in one study (www.mdpi.com).

Product purity: amine or hot‑carbonate absorption yields essentially pure CO₂ (post‑condensation) and a clean H₂ stream. PSA delivers 99.3% pure H₂ in the cited case (www.mdpi.com) and routinely >99.9% H₂ in commercial practice (www.airproducts.ie).

Energy: hot K₂CO₃ sits around ~2.2–2.5 GJ/tCO₂ heat plus ~770 kWh/t electricity (emis.vito.be). MDEA/Pz is ≈3.2–3.6 GJ/tCO₂ in base cases (www.researchgate.net) (www.mdpi.com), reducible toward ~2.8 GJ/tCO₂ with advanced cycles (www.researchgate.net). PSA is driven mainly by electrical energy (compressors/vacuum) and has a much lower thermal duty.

Cost: hot K₂CO₃ capture comes in around ~55–84 €/tCO₂ based on EMIS CAPEX/OPEX entries (emis.vito.be). MDEA/Pz is often ≥70–100 €/tCO₂ (with flue‑based chemical capture analyses reaching higher). PSA can be highly competitive — about £17/tCO₂ in one steel gas analysis (www.mdpi.com) — but actual economics depend on local energy prices and scale.

Scale: amine units span from modest (~10 MMSm³/d) to very large trains. Hot‑carbonate favors large syngas flows (many patent plants >100 MMSm³/d since the 1960s). PSA modules cover ~1,000 to >100,000 Nm³/h feed rates, with parallel trains available (www.airproducts.ie).

Plant size and flow regime

Small ammonia plants (e.g., <100 tpd NH₃; tpd means tonnes per day) often favor solvent units because PSA beds have a minimum practical size (~1–10 ktpa H₂). Larger sites (several hundred kta NH₃) can justify PSA’s higher capex with throughput. A rough rule cited in practice: below ~30–50 MMSm³/h (million standard cubic meters per hour) syngas flow, amines are common; above that, either solvent or PSA can be used.

Energy costs and heat integration

If low‑pressure steam (about 10–15 bar) is plentiful or cheap fuel is available, solvent regeneration is attractive. If electricity is very cheap/green, PSA’s electric drive looks better. Co‑generation favors heat‑driven capture (amines/carbonate); constrained steam pushes toward PSA plus mechanical compression. In one analysis of a 100 kNm³/h (thousand normal cubic meters per hour) H₂ + PSA plant, MDEA stripper steam dominated energy use, so cutting steam duty was prioritized (www.mdpi.com).

CO₂ and hydrogen product strategy

When the goal is pure CO₂ (for urea synthesis or sale), solvent systems naturally deliver a CO₂ stream that condenses to near‑100% purity. PSA’s CO₂ exits at moderately high pressure, which is advantageous if compressing for storage. If the target is ultra‑pure hydrogen, PSA excels at 99.9%+ H₂ purity (www.airproducts.ie). Amine purification yields H₂ with a few ppm CO₂/N₂, typically acceptable for Haber (which tolerates ~3% inert H₂ by volume).

Operating complexity and retrofit

Solvent circuits require careful corrosion and contaminant management and employ tall towers with trays or structured packing. PSA systems demand precise valve sequencing and adsorbent conditioning. In revamps, adding a PSA skid can force substantial piping and control changes; conversely, upsizing an absorber/stripper may be constrained by plot space or steam supply.

Policy signals and market context

Regions with carbon pricing or CO₂ utilization mandates are pushing “blue ammonia” strategies. For example, Indonesia’s producers are expanding clean ammonia to meet Japan/Korea demand (www.reccessary.com). A solvent train achieving ~95+% capture supports compliance; PSA’s high capture (up to ~100%) maximizes CO₂ for sequestration, though tail‑stream management is key.

Worked selection examples

A 200 ktpa NH₃ plant (roughly 220 t/d H₂) may adopt a hybrid: use an activated MDEA/Pz absorber for bulk CO₂ removal down to <0.1% CO₂ to protect catalysts, then polish hydrogen via PSA to hit 99.9%+ H₂ if required. A smaller 50 ktpa plant can keep it simple with MDEA in a downflow‑tray absorber. If energy prices diverge (e.g., natural gas at $3/MMBtu versus electricity at $0.03/kWh), the cut‑over between amines and PSA — or hot carbonate vs MDEA — often falls in the few‑tens of MMSm³/h range.

Conclusion and operating scale

Activated MDEA and hot K₂CO₃ are proven large‑scale scrubbers delivering ≈80–95% CO₂ removal with ~2.2–3.5 GJ/tCO₂ steam demand (www.researchgate.net) (emis.vito.be). PSA offers a solvent‑free, electric‑driven alternative that can directly yield >99% H₂ and ~97% CO₂ streams (www.airproducts.ie) (www.mdpi.com). The choice comes down to throughput, the local price of steam vs electricity, and product targets; smaller, heat‑integrated plants often run amine/carbonate, while large or CSR‑driven (“blue ammonia”) projects increasingly look at PSA or hybrids.

Context and figures

Global ammonia capacity (~140 Mt/yr) implies hundreds of CO₂ removal trains in service (www.sciencedirect.com). CO₂ capture costs and the energy penalty remain central levers in decarbonization and “blue” ammonia initiatives (www.mdpi.com) (www.reccessary.com).

Sources and metadata

Su, W. et al., Applied Energy 259 (2020) 114135. “Techno-economic comparison of green ammonia production processes.” DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.114135 (www.sciencedirect.com).

Moioli, S. & Pellegrini, L., Energies 17 (2024) 3089. “CO₂ Removal in Hydrogen Production Plants.” DOI:10.3390/en17133089 (www.mdpi.com) (www.mdpi.com).

Khan, B. A. et al., Sustainability 12 (2020) 8524. “Energy Minimization in Piperazine-Promoted MDEA-Based CO₂ Capture.” DOI:10.3390/su12208524 (www.researchgate.net) (www.mdpi.com).

EMIS (European Institute for Industrial Sustainability) Techno‑Economic Database, “Hot Potassium Carbonate Process,” accessed 2024: capture efficiencies, energy duty, CAPEX/OPEX data (emis.vito.be) (emis.vito.be) (emis.vito.be).

Air Products Ltd., “Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) Hydrogen Purification,” product brochure: >99.9% H₂ purity and modular PSA flows (www.airproducts.ie).

Bashir, F. I. et al., Energies 18 (2025) 2440. “Performance and Cost Analysis of PSA for H₂, CO, and CO₂ Recovery from Steel Off-Gases”: 99.3% H₂ at 80% recovery; 96.9% CO₂ at 75% recovery; CO₂ cost ~£17/t (www.mdpi.com).

Reccessary News, “Pupuk Indonesia expands clean ammonia production…,” June 19, 2024 (www.reccessary.com).