Two shift converters—hot iron up front, cool copper at the back—turn carbon monoxide into carbon dioxide and hydrogen. The catch: keep the steam-to-gas ratio tight and sulfur/chlorine near zero, or conversion (and catalysts) suffer fast.

Industry: Fertilizer_(Ammonia_&_Urea) | Process: Synthesis_Gas_Production

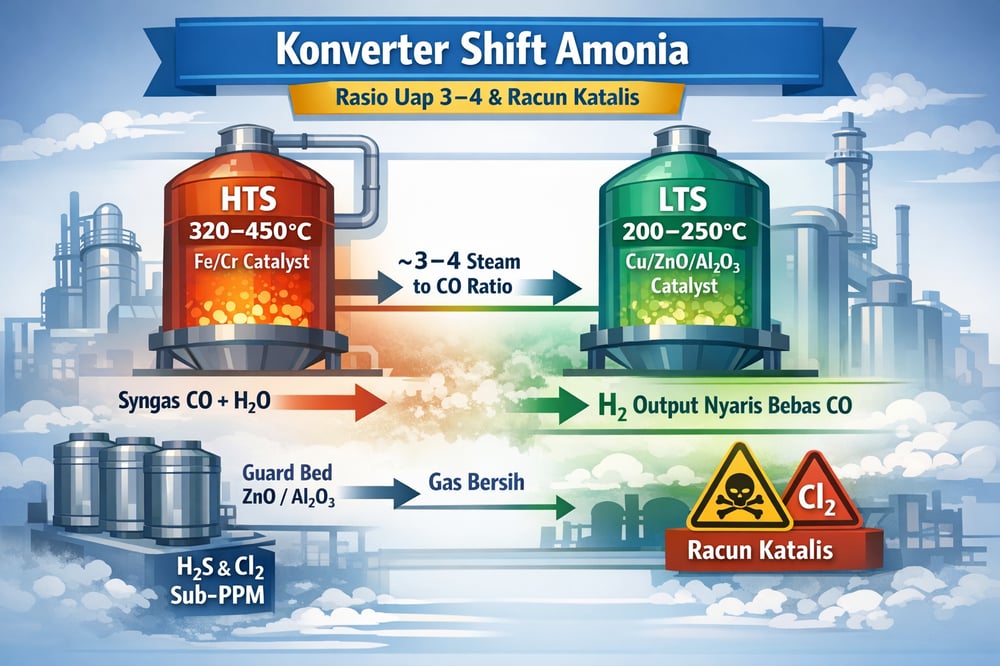

The water‑gas shift (WGS) reaction—CO + H₂O → CO₂ + H₂—does the heavy lifting after reforming in ammonia/urea syngas production. It’s exothermic (releases heat) and industrial plants run it in two stages: a high‑temperature shift (HTS) at ~320–450 °C over iron‑based catalysts (Fe₂O₃–Cr₂O₃ with K₂O promoter) and a low‑temperature shift (LTS) at ~150–280 °C over copper‑based catalysts (Cu/ZnO/Al₂O₃) (pubs.acs.org) (www.mdpi.com).

The two‑stage train is deliberate: the HTS front end rapidly converts most CO at higher temperature (and relatively lower steam), while the LTS “polishes” the remainder to trace levels. In one plant analysis, syngas leaving HTS still had ~3.60% CO, which fell to ~0.40% after LTS (www.azom.com) (www.azom.com). In lab work, a Cu/ZnO/Al₂O₃ catalyst hit ~94.8% CO conversion (CO₂ yield ~59.2%) at 333 °C, essentially at equilibrium when well pretreated (www.mdpi.com).

In practice, overall CO conversion in a two‑stage shift can exceed 90–95%, producing nearly CO‑free H₂ for ammonia synthesis (www.azom.com) (www.mdpi.com).

Two‑stage shift train and catalysts

HTS catalysts (Fe–Cr) are chosen for rate and compact reactors at ~320–450 °C, but equilibrium limits prevent full conversion at those conditions (pubs.acs.org) (www.mdpi.com). LTS (Cu–Zn) at ~150–280 °C then brings CO down to trace levels (www.mdpi.com).

Modern operating pressures are well established: HTS at 20–30 bar, LTS at ~20–25 bar. Catalyst beds, using proven proprietary formulations, are designed to achieve >90% CO conversion, and advanced Cu–Zn formulations retain significant activity even below 250 °C, with effluent CO approaching the low‑ppm (parts per million) levels demanded by ammonia synthesis (www.mdpi.com).

The recycled gas composition tells the story: hydrogen rises slightly and CO₂ rises, while CO drops from several percent to sub‑percent after LTS; in the cited case CO went ~3.60% post‑HTS to ~0.40% post‑LTS (www.azom.com) (www.azom.com).

Steam‑to‑gas ratio as a conversion lever

WGS yield is strongly driven by the steam‑to‑CO ratio (often discussed as a steam‑to‑carbon, S/C, ratio). A higher steam ratio pushes equilibrium toward CO₂ and H₂, maximizing CO conversion (www.mdpi.com) (gasprocessingnews.com). Industry practice targets S/C ≈3.0–4.0; Baraj et al. (2022) note a steam/CO ratio of 3–4 is “suggested” for optimal WGS performance (www.mdpi.com). Guidance for hydrogen/ammonia plants likewise confirms S/C ≈3.0 as a global standard (gasprocessingnews.com).

Below that, CO conversion drops and undesirable carbon (coke) formation can occur; above it, extra fuel is wasted generating steam. A survey of ammonia plant streams cites a minimum of 3.0 lb‑moles steam per 1.0 lb‑mole carbon “to prevent coking” (www.azom.com).

Quantitatively, raising S/C from 2 to 3 might improve CO conversion on the order of 10–20% (e.g., from ~80% to ~95%), though returns diminish past ~3–4. Plants hold the setpoint tightly: on‑line analysis can maintain S/C within ±0.02% (www.azom.com). Excess steam (S/C ≫ 4) yields little extra H₂ and wastes energy; too little (<3) risks methane or carbon deposition on reformer and shift catalysts (www.azom.com).

There’s also a kinetic trade‑off: high steam dilutes the gas and lowers CO partial pressure, slowing reaction rates, so optimal design balances equilibrium and kinetics. Empirical plant data show that with adequate steam, hydrogen content rose from 52.7% (HTS) to 54.2% (LTS) in one mass spectrum analysis (www.azom.com) (www.azom.com).

Low‑temperature copper catalysts and poisons

Cu–Zn–Al LTS catalysts are highly efficient but extremely vulnerable to impurities: sulfur compounds (H₂S, mercaptans) and chlorides (e.g., HCl) will irreversibly deactivate copper even at trace levels (www.azom.com) (www.mdpi.com). In practice, WGS feed gas must be scrupulously cleaned upstream to reduce H₂S to “sub‑ppm” concentrations (ppm = parts per million).

Bench tests underline the sensitivity. When a lab Ni/Fe shift catalyst saw 0.4 mol% H₂S (4000 ppm), >90% of the H₂S was immediately adsorbed, and CO conversion fell to ~86% from near‑complete; a Cu catalyst in parallel remained ~94% active during that test, but the bed captured about 13.6 wt% sulfur (≈6.8 g) as metal sulfide (www.mdpi.com) (www.mdpi.com). For a Cu–Zn catalyst at 0.4 mol% H₂S, 2.5 wt% S deposited (presumably as Cu₂S), effectively poisoning copper surface sites (www.mdpi.com).

Mercaptans and H₂S similarly bind to Cu sites, often forming COS and gradually shutting down WGS activity (www.mdpi.com) (www.mdpi.com). One industry source is blunt: promoters of shift systems must “analyze the feed stream for sulfur‑containing components such as hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans, which are poisons and will de‑activate the catalyst” (www.azom.com).

Chlorine is equally problematic. HCl will react with Cu to form copper chloride or oxychloride, destroying active sites. Experienced operators require HCl in syngas to be negligible (often <0.1 ppm) before LTS; even <1 ppm H₂S can shorten LTS catalyst life.

Gas cleaning, guard beds, and scrubbing

Because of this sensitivity, industrial syngas cleaning is mandatory before LTS—“steam/gas ratio in spec” is not enough; syngas purity is equally critical. Plants deploy guard beds (ZnO, CdO, activated alumina) to scrub H₂S/HCl and often use amine scrubbers to cut sulfur to sub‑ppm (www.mdpi.com). In practice, that can include amine solvents such as amine‑based CO₂/H₂S removal media.

Tests with chlorine‑laden gas (or after partial Cu poisoning) show drastic drops in CO conversion at low LTS temperatures (試). Experimental poison studies also report that a Cu‑based LTS bed can adsorb >90% of incoming H₂S—alongside rapid activity loss if exposure continues (www.mdpi.com) (www.mdpi.com).

Operating window and performance metrics

In modern practice, HTS is run at 20–30 bar and LTS at ~20–25 bar. With bed design targeting >90% CO conversion and advanced Cu–Zn catalysts retaining activity below 250 °C, LTS effluent CO approaches low‑ppm territory (www.mdpi.com). Real‑world gas analyses show the transition: CO dropping from ~3.60% post‑HTS to ~0.40% post‑LTS, with H₂ and CO₂ rising slightly (www.azom.com) (www.azom.com).

That aligns with laboratory evidence where activated Cu catalysts achieved ~94.8% CO conversion (CO₂ yield ~59.2%) at 333 °C, essentially on equilibrium for well‑pretreated copper (www.mdpi.com). Catalyst beds are configured with proprietary formulations specifically to exceed 90% conversion in two‑stage service.

Regulatory context and emissions discipline

Local rules reinforce the engineering: Indonesia’s Permen LHK 17/2019 (“Baku Mutu Emisi”) sets strict emission limits for fertilizer/ammonium industries, implying upstream H₂S and Cl must be minimized and pieced out in the shift section to meet environmental limits (peraturan.bpk.go.id).