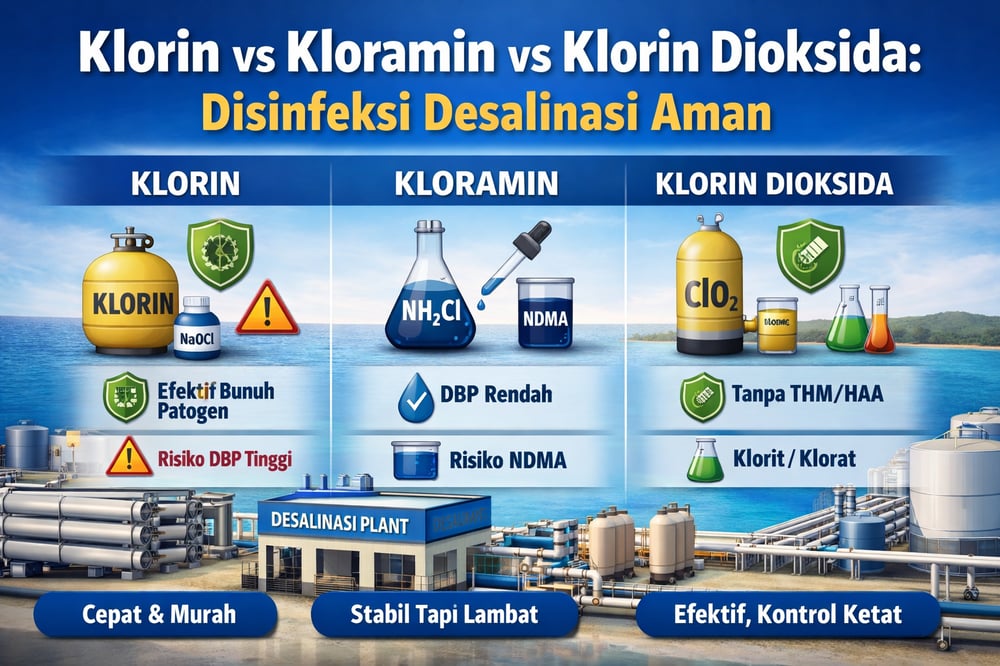

Desal plants live and die by their final disinfection step: kill pathogens fast, keep a stable residual in the network, and keep disinfection by‑products (DBPs) below tight limits. The choice between chlorine, chloramines, and chlorine dioxide decides how well those goals are met—and what trade‑offs operators must manage.

Industry: Desalination | Process: Post

Desalinated water requires robust final‑stage disinfection to ensure microbiological safety in distribution, while also complying with DBP regulations. Free chlorine (hypochlorous acid/hypochlorite, HOCl/OCl⁻) remains the most common disinfectant because it provides rapid, broad‑spectrum inactivation of bacteria and viruses and is inexpensive (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au).

But free chlorine reacts with trace organic matter, and in seawater contexts with bromide or iodide, to form halogenated DBPs—particularly trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (HAAs)—and, with bromide/iodide, more toxic brominated/iodinated DBPs (researchgate.net; pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Untreated seawater can contain bromide up to tens of mg/L; even after reverse osmosis (RO), 250–600 µg/L bromide may remain, and chlorination of such water produces brominated DBPs that have been shown to be genotoxic (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Reviews note that disinfectants (Cl₂, chloramines, O₃, ClO₂) react with natural organic matter (NOM), bromide and iodide to form a complex DBP mixture in the final product (iwaponline.com).

Regulatory standards reflect these risks. The US EPA caps total THMs (TTHM) at ≤80 µg/L, HAA₅ at ≤60 µg/L, bromate at ≤10 µg/L, and chlorite at ≤1.0 mg/L; Indonesian Permenkes 492/2010 sets TTHM ≤100 µg/L (water.co.id). Public health guidance from Australia and WHO emphasizes that pathogen control must not be compromised for DBP control—adequate log‑reductions of bacteria and viruses are paramount, and DBP compliance is managed via process design (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au).

Free chlorine performance and by‑products

Use case: Free chlorine—typically as Cl₂ gas or sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl)—is often both the primary disinfectant and the residual, commonly maintained at 0.2–0.5 mg/L as Cl₂, because it achieves rapid microbial inactivation at low “Ct” (concentration × time) and also oxidizes iron and manganese (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au). In seawater RO trains, such as SWRO systems used in industrial or power contexts, operators typically manage post‑treatment exposure to balance residual maintenance and DBP control.

DBPs: Reaction with residual organics generates THMs and HAAs. In high‑bromide waters this yields brominated THMs (e.g., bromoform) and HAAs. Seawater chlorination can produce a wide array of DBPs—THMs, HAAs, halonitromethanes (including haloacetonitriles), iodinated THMs/HAAs, haloketones, N‑nitrosamines (NDMA), plus bromate and chlorite from inorganic precursors (researchgate.net). One Gulf plant reported RO feed THMs of 490–680 µg/L and HAAs 69–175 µg/L under chlorination, versus only 2–6 µg/L THMs and 1–2.5 µg/L HAAs in permeate—about 99% removal by RO (iwaponline.com). The fraction of THMs that are brominated or iodinated is particularly toxic (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; iwaponline.com).

Advantages: Chlorine is easy to dose and monitor (residual is a direct indicator), highly effective against bacteria and viruses, low cost, and has a long safety record (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au). Shock dosing provides immediate response.

Drawbacks: Polymeric membrane systems cannot be exposed to residual chlorine because of damage; post‑RO chlorination is therefore done after membranes and often followed by dechlorination if needed. High chlorine doses increase THM/HAA formation (proportional to dose × TOC × contact time). Chlorine is relatively ineffective against Cryptosporidium at practical doses (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au). Bromide can be oxidized to bromate (regulated at 10 µg/L), especially by ozone but also by Cl₂ under high‑pH or high‑dose conditions. Where dechlorination is required ahead of membranes, operators turn to specialty agents such as dechlorination chemicals to protect downstream stages.

Chloramines as network residuals

Use case: Monochloramine (NH₂Cl), formed by dosing chlorine plus ammonia, is mainly a residual disinfectant for distribution because it is much more stable in the network, with lower decay and fewer taste/odor issues. Systems often apply a chloramine residual of 1–2 mg/L as Cl₂ after initial free chlorine disinfection in a “two‑stage” approach (pdfcoffee.com).

DBPs: Chloramination dramatically lowers THM and HAA formation versus free chlorine—often by more than 80%—because monochloramine is a weaker oxidant and less reactive with NOM (pdfcoffee.com). However, chloramine chemistry yields nitrogenous by‑products, most notably NDMA (N‑nitrosodimethylamine), a potent carcinogen. NDMA forms when chloramines react with certain amine precursors; even µg/L‑level yields matter given that California’s goal is ~3 ng/L (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Experiments on blended seawater/wastewater disinfection show nitrogenous by‑products (including NDMA) forming under bromochloramine conditions (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Advantages: Chloramines provide a long‑lasting residual maintained over days, inhibiting biofilm regrowth in long distribution lines, and they improve aesthetics with less “chlorine smell” while yielding much lower regulated DBPs (pdfcoffee.com).

Drawbacks: Monochloramine is a weaker disinfectant; achieving comparable microbial kill requires 5–10× longer contact times, particularly for viruses and protozoa. It cannot quickly inactivate Cryptosporidium or some viruses at feasible doses, fosters nitrifying bacteria (necessitating careful ammonia control), and poses a risk for dialysis patients. NDMA formation, usually at ng/L levels, is the key concern and may require specialized monitoring or additional treatment (e.g., UV/AOP) if elevated (pdfcoffee.com).

Chlorine dioxide for selective oxidation

Use case: Chlorine dioxide (ClO₂) is a powerful, selective oxidant used—often with on‑site generation—to inactivate bacteria and viruses and control biofilm without forming THMs. It is effective at 0.5–2 mg/L with short contact times (<30 minutes), is largely pH‑independent, and decays to chlorite/chlorate.

DBPs: ClO₂ does not form THMs or HAAs. Its primary by‑products are chlorite (ClO₂⁻) and chlorate (ClO₃⁻), which have their own risk profiles. The EPA Stage 1 DBP Rule limits chlorite to 1.0 mg/L, and chlorate is an emerging concern; WHO (2022) sets chlorite at a provisional 0.7 mg/L guideline value (pdfcoffee.com). ClO₂ can also produce small amounts of bromite from bromide.

Advantages: No THMs or HAAs; strong performance against bacteria and viruses at low concentrations; good oxidation of iron/manganese and taste/odor compounds; effective short‑term biocide for biofilm control.

Drawbacks: ClO₂ gas is explosive and must be generated on‑site. It leaves no persisting disinfectant, so systems often add a small free chlorine or chloramine residual downstream. Chlorite/chlorate remain in water and must be controlled by limiting dose or removing with carbon; slight chlorite taste/odor can occur; some jurisdictions restrict ClO₂ use or require extra monitoring.

DBP formation pathways and controls

All disinfectants form some by‑products when reacting with remaining organics or inorganics. Key DBP classes in desalinated water include: THMs and HAAs from free chlorine—whose brominated/iodinated analogues are more toxic—with TTHM/HAA₅ limits as above (water.co.id); nitrosamines (NDMA, NDEA) from chloramine or chlorine reacting with trace amines; halonitromethanes, haloacetonitriles, haloketones as minor products; bromate if ozone is used on bromide‑containing water; and chlorite/chlorate from ClO₂ and from hypochlorite decay under poor storage conditions.

Membranes remove many DBPs formed upstream: RO can strip more than 99% of THMs and HAAs produced earlier (iwaponline.com). In practice, pretreatment trains target DBP precursors before final disinfection. Coagulation, granular activated carbon (GAC), and ion exchange (e.g., MIEX) to reduce total organic carbon (TOC) substantially cut DBP formation potential (water.co.id). Plants routinely design pretreatment around ultrafiltration membranes for solids control and pathogen removal; for that duty, many employ UF units ahead of RO.

Operational levers matter. Moving chlorination downstream (after wastewater reuse facilities/RO) limits precursors’ exposure; dosing lower chlorine with longer contact can minimize peak DBP levels; if DBPs approach limits, operators switch to alternates (UV/advanced oxidation processes or ozone) to avoid chlorinated organics—while recognizing ozone generates bromate if bromide is present—and use chloramines to avoid THMs at the expense of NDMA risk (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au). Australian guidance underscores not compromising disinfection to reduce DBPs and notes that if DBPs exceed guideline values, plants “should be reviewed,” for example by adding carbon adsorption or changing disinfectant (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au). As a polishing step for DBP reduction, GAC beds are common; many facilities deploy activated carbon media after oxidation stages.

Membrane choice and system design also shape outcomes. Reverse osmosis is central, whether in integrated membrane systems or specific trains like brackish-water RO, because RO dramatically reduces organics and bromide compared with feedwater, lowering DBP formation potential downstream.

Strategy selection by water quality and rules

Water quality factors: Feedwater chemistry and distribution needs drive disinfectant choice. High NOM or color in blended water points to strong oxidants upstream (ozone or ClO₂) combined with precursor removal. High bromide/iodide suggests avoiding ozone/chlorine (to prevent bromate/iodo‑DBPs) or using off‑gas scrubbing. Ammonia in product water favors chlorination to avoid forming chloramines unintentionally, or demands precise NH₃ control if chloramination is used. Long networks or large storage volumes favor chloramines for a persistent residual, while Cryptosporidium risk calls for either high free chlorine contact or non‑halogen methods (UV/AOP), since chloramines and low‑dose Cl₂ are inadequate (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au). Where non‑halogen barriers are used, utilities often integrate UV systems into the post‑treatment train.

Regulatory requirements: Local standards set hard boundaries. Indonesian Permenkes 492/2010 mandates TTHM ≤100 µg/L (even after blending), bromate ≤25 µg/L, and chlorite ≤200 µg/L. If ClO₂ is used, operators must hold chlorite below 1 mg/L (EPA) or 0.7 mg/L (WHO). If chloraminating, agencies may require NDMA measurement and prohibit dichloramine formation. Residual requirements typically specify ≥0.2 mg/L Cl₂ at the most distant point; dosing must ensure that target is met.

Technical and cost considerations: Chlorine (gas or bleach) is cheapest and simplest but requires corrosion safeguards. Chloramination needs ammonia feed control and more complex monitoring of chlorine:N ratio and breakpoint. ClO₂ requires a generator, strict operator safety, and close by‑product monitoring. Ozone and UV are non‑chemical options for primary disinfection but provide no persistent residual and carry higher capital costs.

Guidance summary: For rapid pathogen kill, free chlorine at sufficient Ct—or UV/ozone for protozoa—sets the primary barrier; under‑dosing to limit DBPs is not acceptable (guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au). For long distribution, chloramines serve as the stable residual after initial chlorination. If raw or blend water has high TOC, maximize precursor removal first through coagulation, GAC, and ion exchange (e.g., MIEX), using platforms such as ion‑exchange systems to reduce DBP potential. If bromide/iodide exceed ~100 µg/L, expect brominated DBPs under chlorine; using ClO₂ avoids THMs but ozone risks bromate formation. When TTHMs or HAAs are near limits, minimize chlorine contact or pre‑remove precursors; when chlorite/chlorate are regulated, limit ClO₂ dose or add carbon removal.

Case example: A plant blending high‑bromide seawater with treated groundwater might use ozone for residual organics (paired with GAC to handle bromate), then finish with low free chlorine or chloramine for residual. By contrast, a brackish RO facility producing very low TOC permeate might rely on minimal post‑RO chlorine to maintain ~0.5 mg/L residual, with DBP formation negligible.

Across scenarios, a Water Safety Plan approach—measuring DBP precursors (TOC, bromide, ammonia), modeling DBP formation, pilot‑testing disinfectants, and monitoring final DBP species—lets plants balance pathogen reduction targets with DBP risk while staying compliant. For operators augmenting or retrofitting trains, consumables and media such as supporting ancillaries and activated carbon remain central to maintaining performance between audits.

Sources: Peer‑reviewed studies and guidelines from WHO, EPA, AWWA and academic research underpin this analysis (iwaponline.com; researchgate.net; iwaponline.com; guidelines.nhmrc.gov.au; pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).